Trade, Tech & Trump

There is a sense that global activity softened a little in 1Q18 with sentiment knocked by President Trump’s renewed protectionist push. The latest tech-led equity market wobble hasn’t helped either, but the underlying global economic story remains good. While an economically damaging trade war can’t be ruled out, we are hoping calmer heads will prevail we look forward positively to 2Q18.

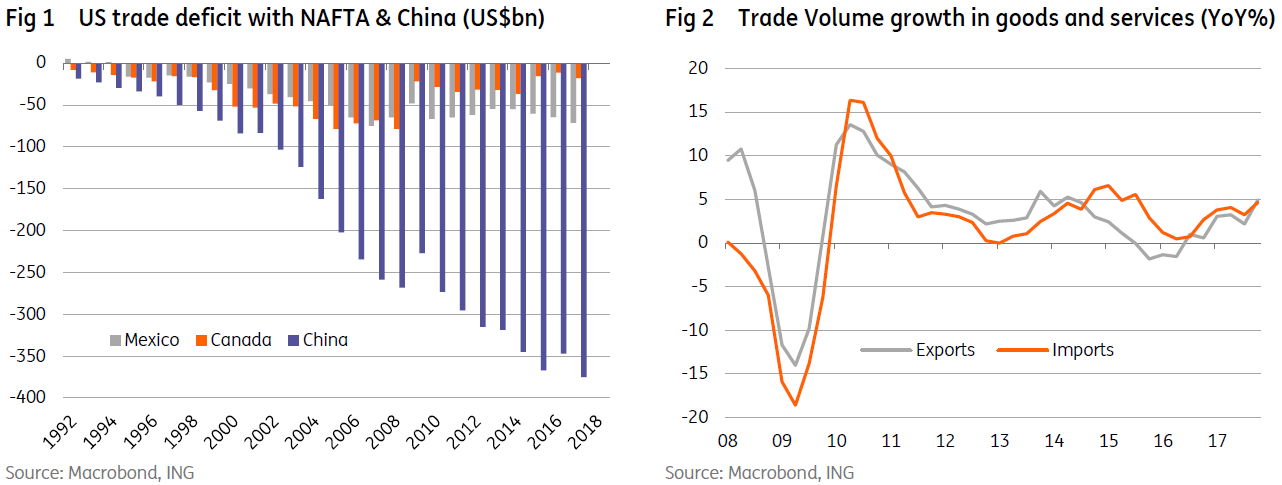

The healthy market glow from President Trump’s tax cuts has swiftly dimmed in the wake of his renewed focus on protectionism. China is clearly in the spotlight with Europe’s temporary reprieve from steel and aluminium tariffs linked to support for pushing China to adopt “fairer” trade practices. The problem is that the huge tax cuts Trump enacted puts more money in the pockets of consumers, much of which will be spent on imported consumer goods. As such we consider it unlikely there will be any meaningful improvement in the overall trade deficit at the end of all of this.

The equity market correction is another issue to watch. It has resulted in part from protectionist fears, but also growing concern over what intensifying regulatory scrutiny for the tech sector might mean. On the positive front, there are signs that Trump is willing to do deals and flexibility from all parties will hopefully avoid an all-out trade war. Given the strong domestic growth story, the competitive exchange rate and a strengthening global economy we are sticking with our 3% US growth forecast for 2018 with three further Fed rate hikes this year.

Even though sentiment in the Eurozone has been sliding, the growth outlook continues to be positive. While the mood is somewhat less “Europhoric” thanks to concerns about the impact of trade uncertainty and some complacency around reform, we still expect growth to come in at 2.4% this year. But despite this, inflation is still not moving towards target. This is causing ECB governing council members to strike a more dovish tone. In our view, the first deposit rate hike is unlikely to come before June 2019 at the earliest.

With one year to go until the UK leaves the EU, talks are entering the most difficult phase yet. But the agreement of a post-Brexit transition period will be welcome news for businesses. Alongside rising wage growth, this makes a May rate hike more likely.

China has responded robustly to US trade measures by announcing its own tariffs on US goods. The signal is clear: China will not be pushed into concessions, and is willing to accept some economic pain in what Beijing may ultimately see as a political dispute. Further retaliatory measures are possible if the US escalates tensions further, but both sides seem willing to negotiate. The question now is whether an agreement that works for both sides can be found.

The White House’s protectionist policies are driving the USD lower against safe haven currencies such as the JPY. We suspect things will get worse before they get better and see outside risk of USD/JPY falling as low as 100. The Eurozone’s huge 3.5% current account surplus also puts pressure on the EUR to appreciate. We still target 1.30/USD.

Despite the big wobbles seen in risk assets, US market rates have managed to maintain reasonable poise. In fact, we continue to expect the 10-year yield to break above 3% over coming months as robust fundamentals, QE unwind and supply measures continue to act as upside forces.

US: Trading down?

President Trump’s renewed protectionist push started off as a relatively minor story relating to imports of solar panels and washing machines but has escalated quickly to one that includes US tariffs on metal imports and key industrial products from China. This is a risky strategy. China has already announced retaliatory measures; if both sides follow through this could undermine business confidence and increase prices, thereby slowing the economy. It could also have broader implications for financial markets and the pace of Fed rate hikes while intensifying downward pressure on the dollar.

President Trump’s initial statement that “trade wars are good, and are easy to win” was quickly followed up with “IF YOU DON’T HAVE STEEL, YOU DON’T HAVE A COUNTRY” as he sought to justify the 25% tariff on imported steel and 10% of aluminium. This presumably came as news to the 70% of the World’s countries that don’t actually have a steel industry but also raised broader questions over the ramifications of risking a trade war for what is now a minor industry.

These two sectors have been under pressure for decades. Just 140,000 people are employed in US steel and 161,000 in the aluminium industry [1], set against the jobs report which showed the US economy created 331,000 jobs in February alone. Moreover, there are 6.5 million US jobs in industries from cars and aircraft to beer cans that are directly impacted by the higher costs from these tariffs.

Questions regarding the efficacy of the tariffs grew more vocal after the Republican Party lost Pennsylvania’s 18th Congressional District to the Democrats in a recent special election. Given Pennsylvania’s long history of coal and steel, the fact Republicans saw what was a near 20% victory margin in 2016 turn to defeat does not bode well for Trump ahead of November’s mid-term elections.

We have subsequently seen NAFTA partners excluded, followed by Australia and European nations. South Korea, Argentina and Brazil are the latest countries to get a temporary exemption. Japan has not, but it is clear that shrinking the US’ $370bn trade deficit with China is the aim.

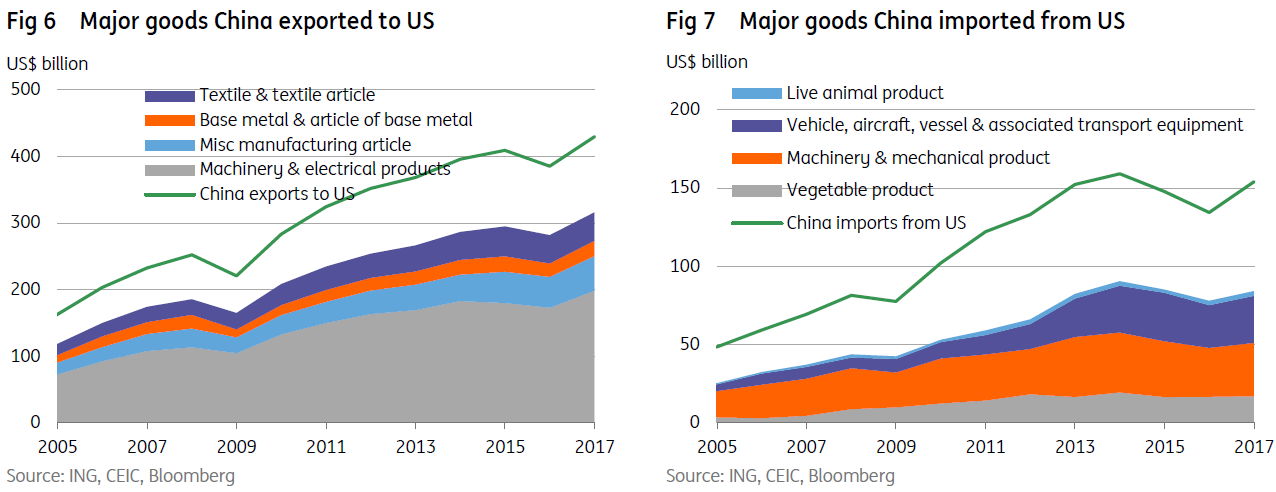

Steel makes up less than 1% of China’s exports, so we have seen an additional round targeting tariffs on US$60bn of Chinese technology, aerospace, electric vehicles and healthcare imports. In addition, US authorities are looking to restrict Chinese investment in sensitive industries while stopping alleged intellectual property thefts.

Chinese officials are at pains to point out that the US$370bn trade deficit figure doesn’t tell the whole story. China imports many sub-components from other countries (including the US) that are then assembled and re-exported to the US. As such, they argue that the “true” deficit is closer to US$150bn. Indeed, their position in supply chains is why, in addition to Trump’s criticism of Amazon and the potential for greater regulatory scrutiny, US tech stocks have been hit so hard in the latest equity market wobble.

Nonetheless, China has responded robustly to US trade aggression by imposing its own tariffs on US$50bn of US exports. The targets include soybeans and other agricultural goods, which are both a major export for the US and particularly sensitive politically given the importance of farm states in the mid-term elections this autumn.

Though this step marks a significant escalation of tensions, both sides have indicated some willingness to negotiate. Media stories about behind the scenes negotiations on technology, Chinese car imports and foreign ownership limits in Chinese companies suggest there is hope that a tit-for-tat trade war can be averted. Nonetheless, this is a politically charged environment, and politicians will be wary of “losing face” at home.

We will have to wait and see if calmer heads prevail and deals can be done that satisfy everyone. Nonetheless, the potential for escalating tensions cannot be ruled out. We have to remember that Canada and Mexico’s reprieve on the steel and aluminium tariffs is only temporary and could be reinstated should they fail to make sufficient concessions in the ongoing NAFTA renegotiation saga. Europe has also been told that the tariffs could come back should they not take steps to help lower the US trade deficit or fail to support the US’ effort to make China adopt “fairer” trade practices.

Consequently, Europe could still carry through with threatened counter tariffs on Harley Davidson motor bikes, Wisconsin cheese (House Speaker Ryan’s home state) and Kentucky Bourbon (Senate Majority leader McConnell’s constituency). But this would then raise the prospect of a new round of tariffs on cars. Cars account for 25% of European exports to the US, and any action here would have severe ramifications.

A full-blown trade war risk putting up prices for consumers while hurting business sentiment and overall economic activity, which would be a drag for asset valuations. Meanwhile, the bond market would be vulnerable to any musings from China on potentially slowing purchases of Treasuries at a time when the US fiscal deficit is heading towards US$1trillion, and the Federal Reserve is shrinking its balance sheet.

Either way, we have our doubts that President Trump’s protectionist initiatives to try and shrink the US’ trade deficit will be very effective. A tight jobs market is putting upward pressure on pay, and Trump’s huge tax cuts are putting on average $900 extra per year in the pockets of US households. Given consumer confidence is at such high levels we suspect much of this extra money will end up being spent on imported consumer goods, which will inevitably keep the trade deficit elevated. Instead, the ongoing downward pressure on the US dollar (see the FX section) is likely to provide a more successful route to ensuring the deficit doesn’t deteriorate significantly from here.

Assuming back-room, face saving deals can be agreed, and trade tensions ease the prospects for the US economy remain very good. Economic activity is strong with business surveys close to all time high levels and the jobs market looking strong. Consequently, we are seeing more evidence of price pressures. As such it was no surprise to see the Federal Reserve hiking interest rates by 25bp in March. We continue to look for three further rate rises this year. For now, we are sticking with two hikes for next year, but if trade fears recede this will be raised to three, taking our forecast for the Fed funds target rate to 3% for end-2019.

James Knightley, London +44 20 7767 6614

Eurozone: Waning confidence

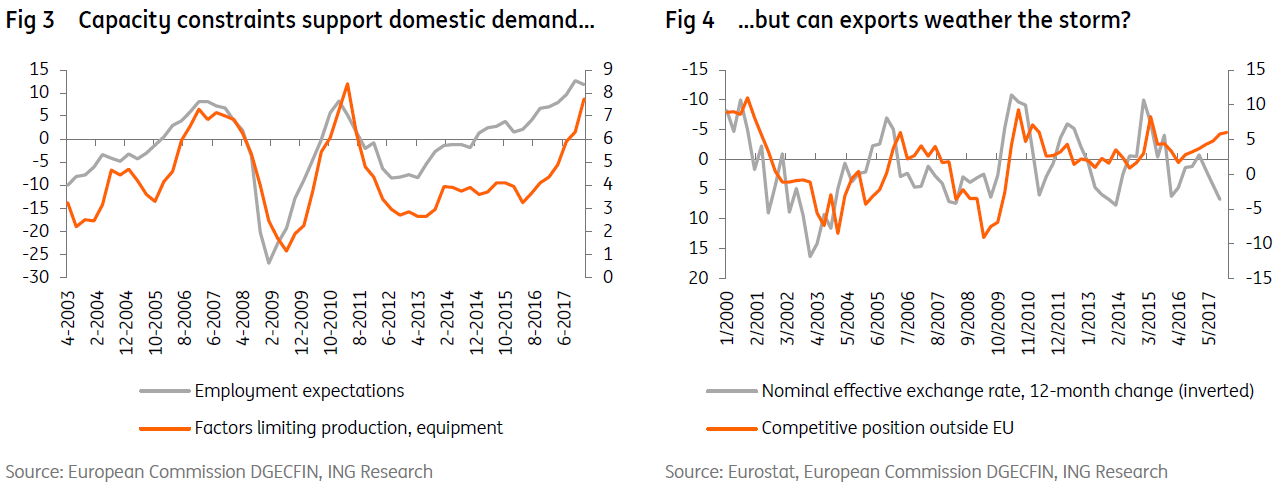

While 2017 could be characterized as the year of “Europhoria”, 2018 has started on a somewhat more cautious footing. Confidence has fallen for businesses in both manufacturing and services in March. Even though Trade Commissioner Malmstrom has arranged an exemption from the tariffs on steel and aluminium for the European Union for the moment, trade concerns seem to be an important driver of the moderating sentiment. The question is how much this is going to impact activity in an economy that seems to be in stellar shape. While economic sentiment has been sliding in 1Q, output measures still indicate strong expansion. Even with lower confidence about future economic activity and moderating growth in new orders, economic growth has probably been strong in 1Q. We expect growth to have come in at 2.5% QoQ annualized.

The outlook for domestic demand continues to be positive as the end of 2017 saw orders come in at such a fast pace that backlogs of work have become significant. Businesses indicate that almost four months of production are assured by current orders, which means that growth is set to remain above trend even if new orders are leveling off somewhat. And while employment expectations have been coming down, they continue to be near all-time highs. This supports consumption in the months ahead as household income improves. Supply constraints also boost the investment outlook as capacity utilization is well above its long-term average and businesses are indicating that a lack of equipment hinders production. Still, as loan growth for non-financial corporates dropped from 3.4% to 3.1% YoY in February, investment growth could become somewhat more modest in the months ahead.

The big question mark is whether export growth can hold up. The continued euro strength has had little impact on export growth so far, and businesses are not yet experiencing a decrease in global competitiveness. Even though exports dropped in January, annual growth of 9.1% outpaces import growth of 6.3% significantly. This January drop in orders New orders for exports are growing at just a slightly more modest pace, indicating that the trade environment has remained benign for now. Whether that remains the case if the EU becomes more involved in a global trade conflict is unlikely, so uncertainty around the outlook for exports has increased. All in all, the growth environment remains healthy, but with a few more ifs and butts attached to it. A slight slowdown in growth in the coming quarters, therefore, seems reasonable, and we had already penciled this in. We, therefore, maintain our forecast of 2.4% GDP growth for the year.

Some reservations about Europhoria might also stem from the political landscape. The grand German coalition will surely cause French president Macron to have a stable and willing partner towards more integration, but the question is whether that will also include reform of the monetary union which seems necessary in the long-run for Eurozone stability. Macron is currently focusing on structural reforms at home, pushing back the Eurozone topics on his political agenda. Given the sensitivity of the matter, agreement between European leaders could sooner be reached on matters like migration, defense and energy. The stance of Italy in that will probably remain uncertain for a while to come. The elections have caused a scattered political landscape with a difficult and long formation ahead. With the populist Five Star movement and Lega as the biggest winners and no obvious coalition emerging, uncertainty about the Italian policy stance remain.

At the March meeting, the ECB again made a hawkish move while striking ever more dovish notes. The removal of the easing bias from the communication was downplayed by President Draghi but was a significant change nonetheless and a clear preparation for the end of QE. The question remains when that is going to happen, and even with the easing bias gone, the ECB does not seem to be in a hurry. They are more and more likely to extend QE further, and even the toughest hawks seem to think so for the moment. We maintain our call of an extension until the end of the year. Inflation data seems to support a more dovish stance for the moment, as core inflation failed to pick up in March despite an early Easter. This usually results in a calendar effect which boosts package holiday prices, but because of lower goods inflation that effect was undone. At 1%, core inflation has not increased since January.

While pipeline pressures had been building over recent months, wage growth continues to be the missing link towards sustainably higher inflation. Even though we were already expecting just a modest pickup in core inflation, it looks like it could be even longer before price pressures start to materialize. This snail-pace improvement in inflation would be in line with a more dovish ECB as it moves towards normalization of its policy. With an extension of QE the most likely option now, that means that hawks are also pushing back expectations of the first rate hike. Bundesbank president Weidmann has expressed comfort with a hike in mid-2019, while Dutch Central Bank President Knot mentioned 2Q. If that is what the hawks think, we feel quite comfortable with the first deposit rate hike happening in June at the earliest.

Bert Colijn, Amsterdam +31 6 30 656 223

UK: Half way there

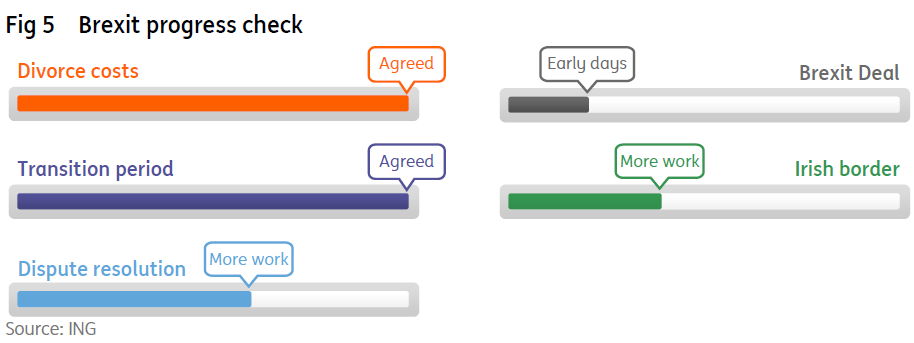

After weeks of deadlock, the March EU summit brought the welcome news that negotiators had reached a deal on a post-Brexit transition period. The agreement, which must still be formally ratified later this year, will create a period of time from the end of March 2019 (when the UK formally leaves the EU) until December 2020 where the UK's relationship with Europe will remain virtually unchanged.

This is good news for businesses. The strong commitment this deal brings will remove a fairly big layer of uncertainty, and should be enough to discourage firms from enacting contingency plans for a ‘cliff edge’ next year.

But as we pass the half-way mark in the Article 50 process, talks are arguably entering their most difficult phase yet. Negotiators have as little as six months to agree on a high level framework for future trade, allowing time for ratification by each individual EU parliament.

As we discussed last month, the UK’s proposals for post-Brexit trade – a model known as ‘managed divergence’ – have so far been met with a cold reception in Brussels. EU officials are fiercely opposed to ‘cherry-picking’ elements from the single market and are cautious about agreeing to a deal that could embolden members of the European Economic Area (EEA) to seek their own concessions, or indeed encourage other EU members to look for the exit. Finding a workable solution to the Irish border is also a major focus, and this will be the sole focus of negotiations over the next month or so.

So the key word over the next six months will be “compromise”. This could see the UK stepping back from key red lines – a tough ask for Prime Minister May given the divisions within her government. But it’s also clear this could be lengthy process, and negotiations on the finer details of the post-Brexit trading relationship could extend well into the transition period. This had got observers and businesses increasingly questioning whether a 21-month transition will be long enough for firms to adapt and for the new customs infrastructure to be built.

In the short-term though, the agreement of a transition period makes the prospect of a near-term rate hike from the Bank of England all the more likely. Officials have long talked-up the importance of having an interim period, and at least for now, it will bolster its assumption that the Brexit process will be “smooth”. This comes as the other key input into the Bank’s thought process – wage growth – continues to show signs of life.

Admittedly, at 2.6%, the current uptick in wage growth says just as much about weakness at the same time last year, as it does about current strength. But even so, the latest numbers indicate that firms are under higher pressure to lift pay to retain/attract talent as the jobs market remains relatively tight. Other surveys paint a similar picture: evidence from BoE agents point to the best year for pay since the crisis, whilst a Markit/REC employment survey recently indicated that starting salaries are rising at the fastest rate in two-and-a-half years.

The combination of Brexit progress and better wage growth figures effectively give the green light on a rate hike at the next meeting in May. The bigger question now is whether they will hike again later this year – markets think it’s roughly 50:50.

This seems about fair, although we currently think the Bank could run into difficulties in hiking beyond the summer. For one thing, the conclusion of Brexit talks in the autumn will almost certainly be a noisy one. And whilst incomes are no longer falling in real terms, they aren’t set to start rising rapidly any time soon either. With consumer confidence not far off post-Brexit lows (at a time when shoppers globally are the most optimistic they’ve been in over a decade), we think overall economic growth will continue to struggle this year.

James Smith, London +44 20 7767 1038

China: Tough on trade game

The Chinese Ministry of Commerce has announced a 25% tariff on US$50bn worth of US exports to China in response to US tariffs on Chinese exports. The tariff measures cover around 100 items including soybeans and some commercial aircraft, both major US exports to the Chinese market. This follows an earlier announcement of tariffs on $3bn worth of goods in response to previous US tariffs on steel and aluminium.

To us, the forceful Chinese response shows three things:

First, China has signalled it is both willing and able to retaliate against US trade barriers. That raises the stakes and increases the risk of escalation of global trade tensions.

Second, like the package the EU floated a few weeks ago in response to US steel and aluminium tariffs, China’s retaliation focuses on US exports that are politically sensitive. Agricultural goods, in particular, are an important target in the run-up to the US midterm elections, where farm states are a key constituency.

Third, China's ambassador to the US has stated that China will fight US tariffs strongly. That could mean China's reaction to US trade tariffs need not end at tariffs but could be expanded to hindering US companies operating in China through non-tariff barriers.

While Chinese employment would be hurt if US companies manufacturing in China decided to move their production lines out of China, this is not likely to happen overnight. And displaced workers could probably find other jobs, likely in the service sector that is booming in China and has low skill requirements.

For transport equipment imports China could find substitutes from Europe and elsewhere. The overall negative impact on China is likely to be mainly through rising prices of these substitutes.

That said, we think China would be reluctant to devalue the yuan to strengthen its competitive position in trade. That would hurt trade relationships beyond the US, and risk wider consequences. We believe that is a last resort measure for China and it will save this option unless the situation becomes much worse.

A key question is whether all this protectionism is at heart an economic or a political issue. The answer carries significant implications. If it is the latter, it could get even more complicated.

Wang Qishan, now the vice president of China, takes the lead on China-US relationship and Taiwan matters. Wang has a reputation as a troubleshooter, taking a robust approach and fixing tricky problems, e.g., managing China’s response to SARS in the early 2000s and most recently leading President Xi’s anti-corruption campaign. We believe Wang will take a tough stance again.

Further action by China will depend on how the US reacts. There are signs that there is a willingness to negotiate on both sides. White House Economic Adviser Larry Kudlow suggested the US tariffs need not be implemented if negotiations can achieve US aims. And China has maintained all along that ‘there are no winners in a trade war’. It remains to be seen whether negotiations can succeed.

Iris Pang, Economist, Greater China, Hong Kong +852 2848 8071

Japan: Political noise

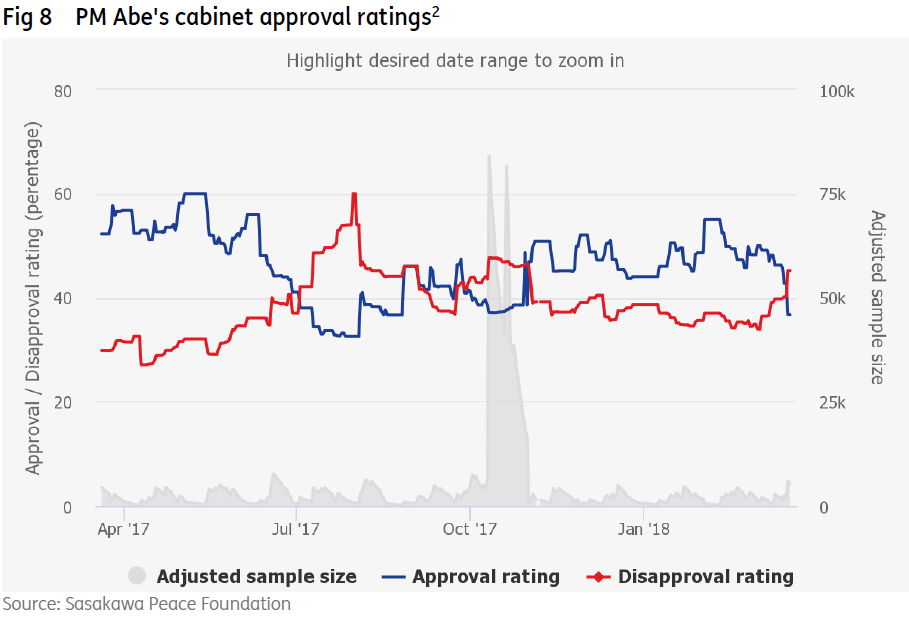

PM Abe’s popularity has taken a further pounding after new allegations surrounding the controversial sale of state land to Osaka-based school operator, Moritomo Gakuen, resurfaced this month.

The background of this case, which has been dogging Abe for some time, stems from public land sales in June 2016 at what appear to be an unusually low price, to Moritomo Gakuen, a Nationalist educating establishment with links to PM Abe’s wife, Akie. Last February, Akie Abe stepped down as honorary governor for the school amidst rising public criticism.

Having allegedly offered to step down as PM if his wife were mentioned in connection to this sale, Ministry of Finance documents surrounding this sale were reputedly destroyed. The re-ignition of this scandal has come from the revelation that other documents related to this transaction may have been doctored by the Ministry of Finance to remove or obscure names. PM Abe has stated in the past that he would resign as PM if his wife were named in the documents.

None of this is helping PM Abe’s desire to amend Japan’s pacifist constitution, with cabinet and personal approval ratings dipping, though still remaining at about 40-42%. Abe’s personal approval ratings are lower.

Japan’s pacifist constitution is something that has stuck in the craw of many nationalist Japanese politicians. But when it comes to the National Self Defence Force, the concept of “armament” seems more of a syntactical distinction than a real goal.

Japan currently spends a little over 1% of GDP on defence, with military spending accounting for about 6.5% of the national budget. This is down on other major countries. Aspirational spending on defence by NATO countries is 2% of GDP. Though few meet this target. But even at 1%, Japan is a big and rich country, and its defence budget is the 8th largest globally, just behind that of the UK.

In terms of concrete forces, Japan has 312,000 Military personnel, of whom a little under 250,000 are active, and the remainder reservist. The infantry is supported by just fewer than 3000 armoured fighting vehicles, of which 700 are combat tanks. And its air force has almost 1600 aircraft, of which around 400 are attack planes and helicopters. Of its 131 naval assets, 4 are aircraft carriers. Destroyers, corvette ,submarines and mine warfare vessels make up the remainder [3].

Until the Moritomo Gakuen scandal is laid to rest, Abe, who faces an election as President of the LDP after his current 3-year term comes to an end in September this year, will struggle to pass any fresh legislation, including on the constitution. And although opposition politics in Japan still look chaotic, this helps the LDP to retain power, not necessarily Abe. Even if Abe survives this current inquest into his and his wife’s role in the Moritomo scandal, a national referendum would be required to make a constitutional change. It currently looks quite unlikely that any such referendum would gain sufficient support to become national law.

Rob Carnell, Singapore +65 6232 6020

FX: Protectionism to dominate

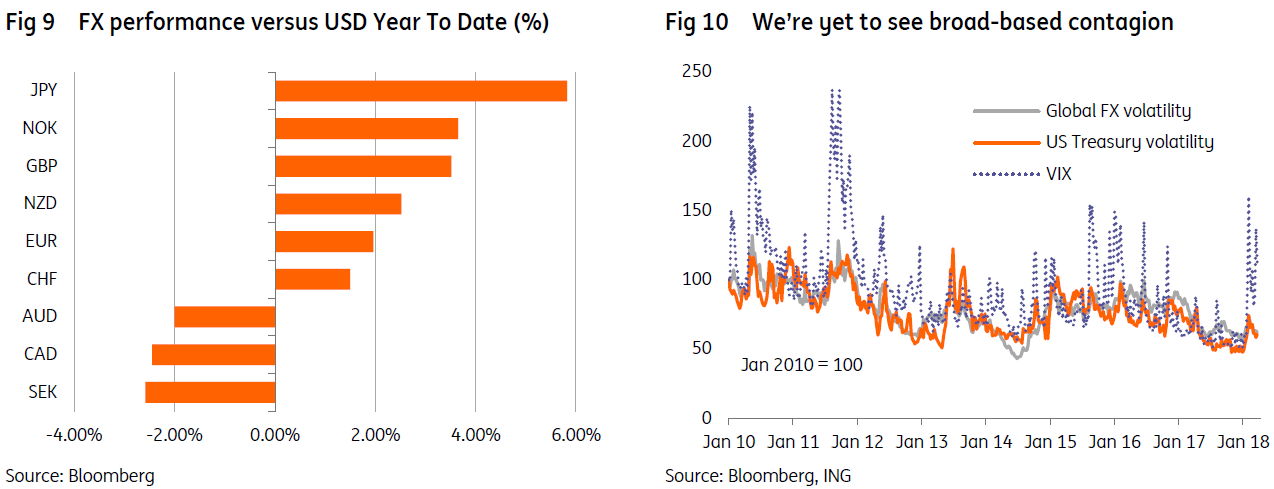

On paper, the loose fiscal and tight monetary policy mix in the US should be good for the dollar. And the recent widening in the USD Libor-OIS spread has only increased USD hedging costs still further – also a dollar positive. Yet the dollar has fallen against most G10 currencies as investors come to terms with Washington’s trade policy. We expect protectionism to dominate markets through 2Q18 and the dollar to stay under pressure against the JPY and the EUR – currencies both backed by large trade surpluses.

None of this year’s JPY out-performance is due to expectations of BoJ normalisation in our opinion. Instead, it is down to the escalation in Washington’s protectionism – from initially protecting narrow sectors to now targeting 1300 Chinese products to redress IPR theft. This seems to be part of a broader national security strategy adopted in late 2017.

Central to this strategy is a view that US trade deficits are a function of unfair practises (included under-valued currencies) amongst trading partners. And like Republican administrations before them, the current White House wants a weaker dollar.

The role of FX in trade tension should come to the fore with the mid-April release of the US Treasury’s semi-annual FX report. We’ve already seen the US Treasury discourage the Bank of Korea from KRW liquidity supplying operations over recent weeks – prompting USD/KRW to fall to a new low for the year. And we expect the tone of the report to be pretty critical of any-one running a large trade surplus with the US.

The Eurozone runs the second largest trade surplus with the US (US$135bn in the 12 months to January), and the Eurozone’s 3.5% current account surplus suggests a very competitive EUR. After the JPY, we do think the EUR can play a role as a safe-haven currency. Equally were protectionism to damage the US equity market and Trump to dial-down protectionism this summer ahead of November mid-term elections, we would also expect the return of monetary normalisation stories to help EUR/USD.

Year-end targets for EUR/USD and USD/JPY at 1.30 and 100 still make a lot of sense to us – with a slight preference for JPY out-performance. This also suggests that the currencies of small, open economies with high export to GDP ratios should underperform – as has been the case with AUD, CAD and SEK so far this year.

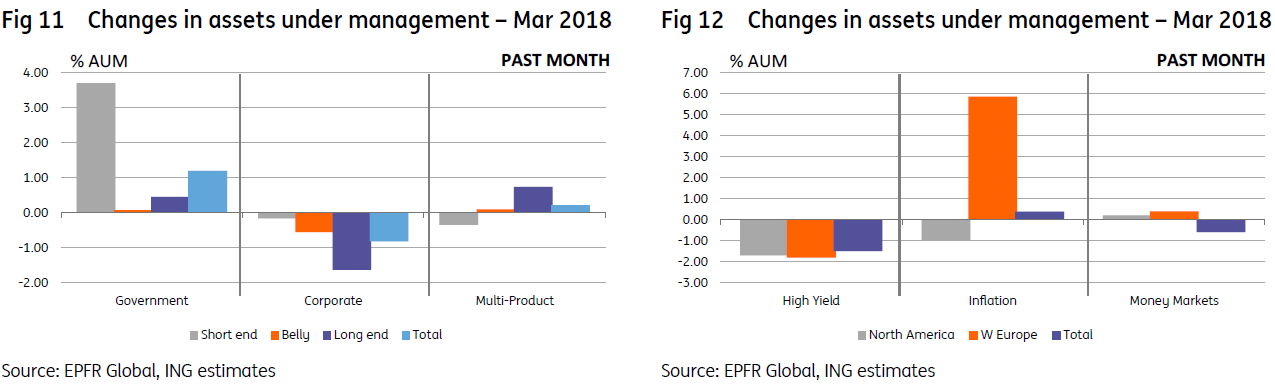

We would also categorize protectionists fears currently as relatively low-level at present. Volatility in equity markets has not filtered through to generalised FX or bond market volatility. Investors believe Trump’s bark is bigger than his bite. This looks complacent.

Chris Turner, London +44 20 7767 1610

Rates: Risk asset wobble

Despite the big wobbles seen in risk assets, US market rates have managed to maintain reasonable poise. Yes, the 10yr yield tested lower through March to trough at 2.73%, but it’s now back above 2.8%. It is still below the big 3% target, but back to within spitting distance of it. Our view remains intact; at some point in the coming months the 10yr yield will likely approach and break above 3%.

We’d, in fact, expect the 10yr to settle in the 3% to 3.5% area, and somewhere within that range is where the cycle peak should mark. The key drivers are three-fold.

- Robust fundamentals, encapsulated by, e.g., consumer confidence readings that are off the charts, in turn tempting the various measures of inflation higher.

- By 4Q this year central banks will no longer be net buyers of government bonds as the ECB tapers to zero and the Fed continues to de-print money.

- The US fiscal deficit will be on the rise, which means more US Treasury supply.

So, when the 10yr gets above 3%, it will likely be there for at least a number of months. But it may also take a period for us to get there in the first place, as some key headwinds are pushing in the opposite direction.

The ratchet higher in US yields has been curbed by a preference for Eurozone market rates to drift lower since peaking in mid-February. This stretched the Treasury/Bund to extremes and consequently coaxed the US 10yr yield lower. Also, the US 10yr yield got to 2.95% quite quickly in any case and was due some consolidation. And the morph into a steady drift lower in core yields was facilitated by the trade war narrative. This uncertain backdrop is still playing out and acting as a constraining factor.

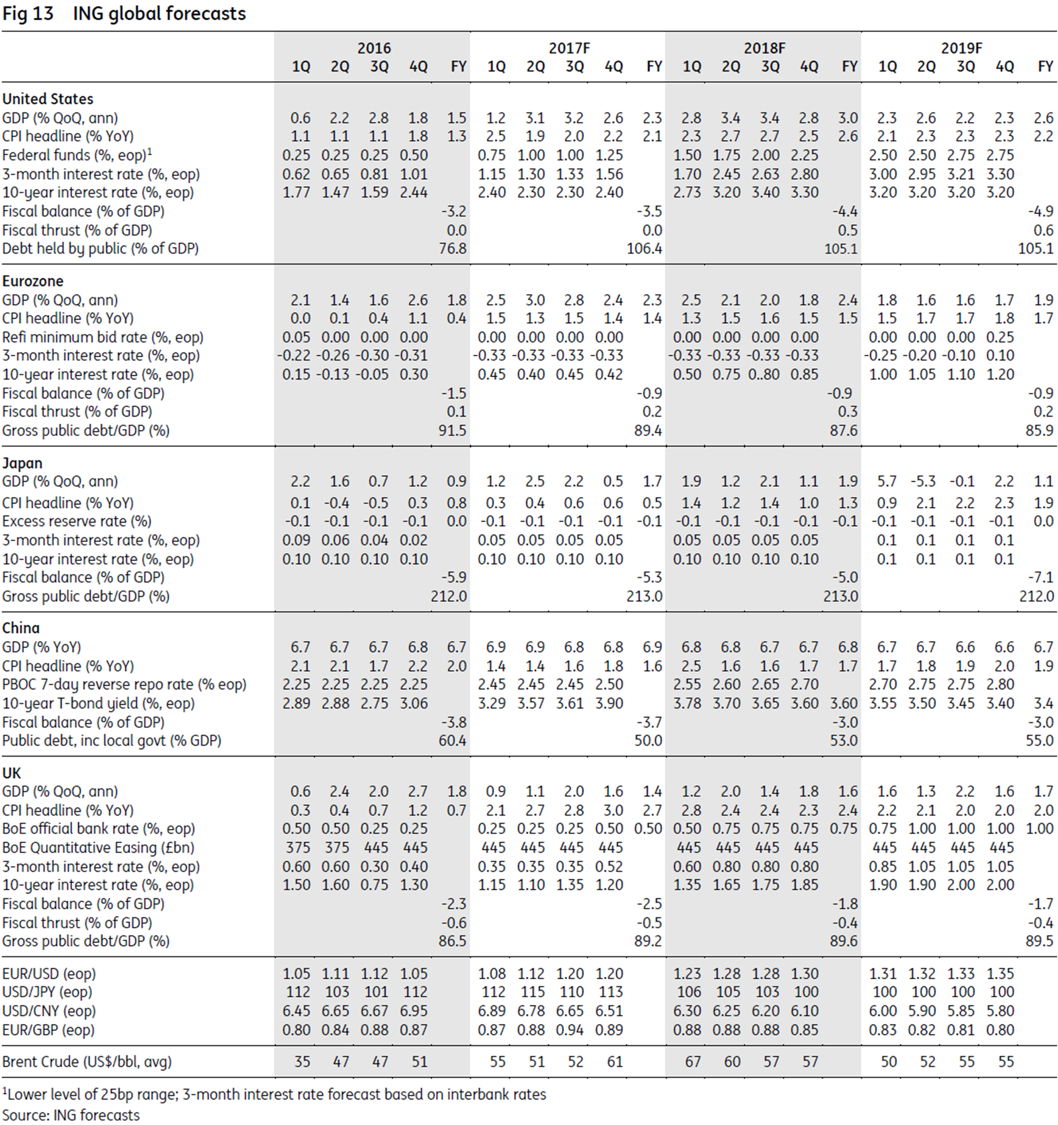

What have market participants been doing in the face of this? There has been a flight into short end government funds and out of long end corporate funds (Figure 11). This implies a short duration strategy – code for positioning for higher rates. Ongoing inflows to W Europe inflation and outflows from High Yield are also thematic (Figure 12). Overall the market is positioning for reflation, higher core rates and wider spreads.

Bottom line, while there is little doubt that contemporaneous macro circumstances are significantly net positive, there are also some quite persuasive naysayers in the wings pointing to issues (e.g. trade war) that can accentuate downside risks to growth. Firm macro prints have assuaged these fears so far, and we expect more in the coming months. Hence 3% remains a credible target for the US 10yr yield. But to breach it, a confluence of positives will likely be required.

Padhraic Garvey, London +44 20 7767 8057

[1] http://abcnews.go.com/Business/key-facts-us-steel-aluminum-industries/story?id=53616380

[2] https://spfusa.org/category/japan-political-pulse

[3] Global Firepower 2017 https://www.globalfirepower.com/country-military-strength-detail.asp?country_id=japan