Still pumping…

Global economic growth is going from strength to strength and price pressures are building. Yet central banks in aggregate are still ‘printing money’ and fiscal policy is increasingly stimulative. This suggests global activity is subject to upside risk and the potential for an old style ‘boom-bust’ cycle may be rising. Central banks will need to tread carefully and markets should prepare for potentially sharp and unexpected changes in monetary policy.

The US economic data for the start of 2018 has been hit by bad weather, but with confidence, incomes and profits at such high levels we remain very upbeat on growth prospects. Tax cuts, looser fiscal policy and infrastructure investment offer further support, but they also add to the threat of a sharper pick-up in inflation and a more rapid rise in interest rates by the Federal Reserve.

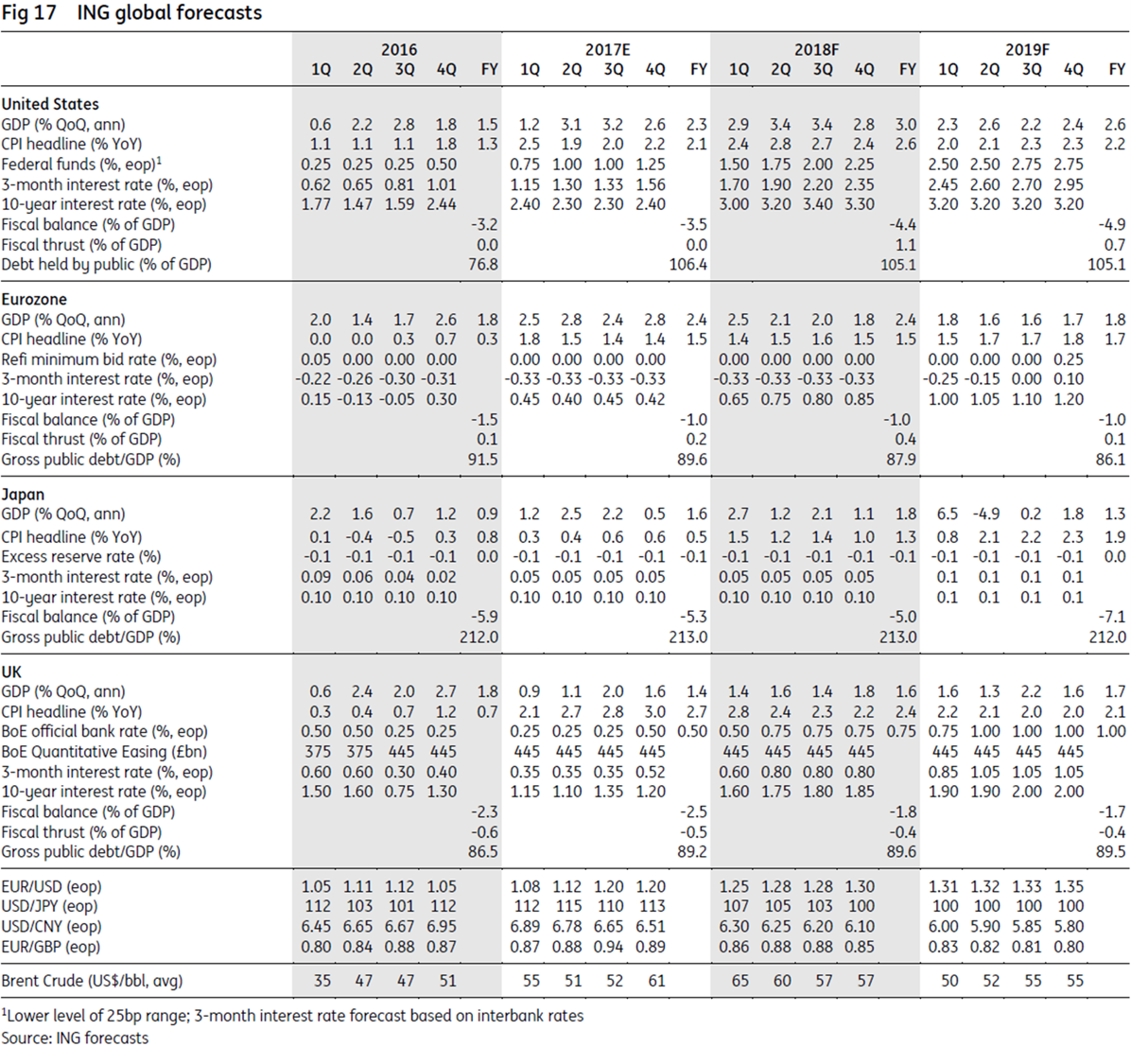

We may also hear more concern over the US twin deficits with the government set to borrow a net $1 trillion next year while the strong consumer sector will continue to suck in imports. We are a little more relaxed on the trade deficit given rising domestic oil output and stronger export demand. However, protectionist policies from President Trump will only intensify market wariness.

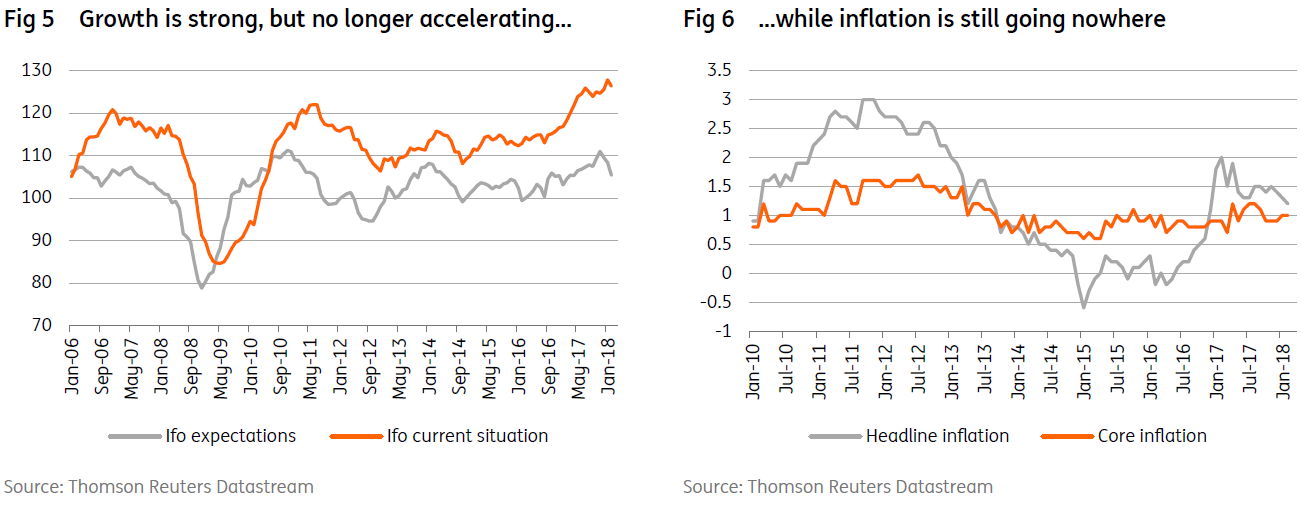

Recent data seem to suggest that Eurozone growth has now reached maximum speed and that the second half of the year might see somewhat slower, albeit still above potential growth. Although some members of the European Central Bank (ECB) Governing Council have been pleading to drop the easing bias in its monetary policy statement, that is unlikely to happen in the short run. Inflation is still going nowhere, while political uncertainty in Italy might push the ECB to tread carefully in determining its exit strategy.

The UK government has finally managed to craft a ‘Brexit’ compromise that ministers can rally around. But the proposals have been met with a cold reception in Brussels, with negotiators viewing the plan as an attempt to “cherry-pick.” Meanwhile, pressure is building on the Prime Minister to look more closely at a customs union as fears about a hard border with Ireland come back to the fore.

Japan’s inflation has risen to levels last seen following consumption tax hikes, with the next tax hike not due until April next year. Collapsing Pacific fish stocks and rising seafood prices, coupled with higher wholesale LNG gas prices are the driving forces. Neither look likely to disappear any time soon. The Bank of Japan (BOJ) may choose not to respond by reducing the pace of its asset buying, but there are other good reasons for it to consider doing so.

President Xi’s longer tenure means stability for the Chinese economy and continuity in economic policies. Foreign countries could feel the heat but that does not necessarily mean trade wars – although US steel and aluminium tariffs increase the risks. The new central bank governor will likely share Xi’s view of a gradualist reform approach. We revise our rate hike predictions to four, matching the US view, and keep our FX forecasts unchanged at 6.1.

FX markets are still coming to terms with the emerging themes of a weaker dollar and a potential rise in asset market volatility – exacerbated by the escalation in US protectionism. The Eurozone’s current account surplus (equivalent to 3.5% of its GDP) should provide good insulation to EUR/USD and we retain a 1.30 year-end target.

US: Dangerous deficits?

In recent years there has been a pattern of heavy winter storms and prolonged snowfall depressing economic activity in 1Q before the data rebounds strongly as the weather improves. 2014 saw GDP contract -0.9% in the first quarter, 2016 saw just 0.6% annualised growth and 1Q17 experienced growth of 1.2%. There was bad weather at the very start of 2018 too, but we are hopeful that disappointing retail sales and industrial production numbers for January will be improved upon in February and March.

Economic momentum appears strong, with business and consumer surveys indicating confidence is high, while tax cuts, looser fiscal policy and President Trump’s infrastructure plans should provide extra support over the next couple of years. The fact that equity markets have recovered most of their losses following the recent correction should also go a long way to ease fears of a negative economic reaction. Consequently, we believe US GDP can still grow close to 3% annualised in 1Q18 and can post 3% for the full year 2018 .

However, we do not subscribe to President Trump’s view that the stimulative benefits from tax cuts and higher spending will offset the near-term hit to government finances. Instead, the prospect of widening fiscal and current account deficits could become an increasingly important topic for financial markets.

We are now looking at a possible $1 trillion government deficit next year, equivalent to around 5% of GDP. This is remarkable given the pace of economic growth and the record levels of employment and corporate profitability. The last time we saw such a disconnect between low unemployment and a widening deficit was in 1968 when the US was spending 9.5% of GDP ramping up the war effort in Vietnam.

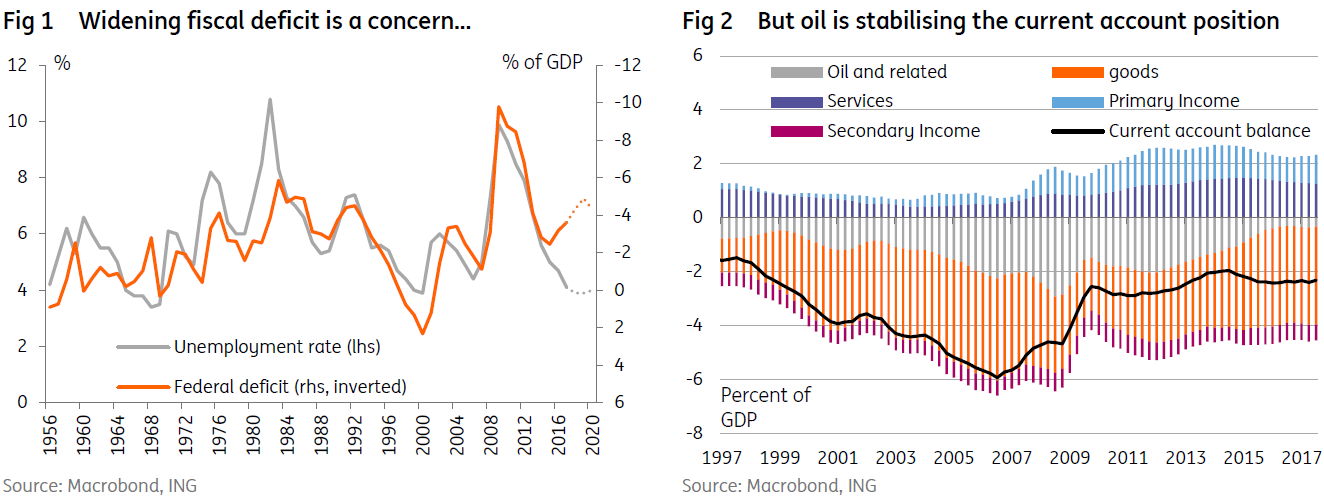

This has contributed in part to the recent sell-off in Treasuries and is leading to more talk about risks for the US dollar. “Twin deficits” on the government fiscal position and the US current account have historically been bad news. However, we expect to see greater stability in the current account than on the fiscal side. The dramatic improvement on the oil balance thanks to US shale output has been a clear positive while the dollar’s fall and stronger external demand should help to stabilise the goods position. Nonetheless, this bears watching, particularly given the uncertainty following President Trump’s announcement on steel and aluminium tariffs and the risk of retaliation.

That said, the near-term economic outlook is very positive, particularly for consumer spending. Wage growth has been the missing link in the strong economic growth, tight jobs market story and it finally looks as though something is happening. The 2.9% YoY reading recorded in January was the highest since June 2009 and is likely to be repeated in February before pushing above 3% in March.

Other evidence backs this story, with the National Federation of Independent Businesses reporting that the net proportion of firms raising worker compensation is at its highest since 2000. Their membership also suggested we have to go all the way back to 1989 to find when the net proportion of businesses planning to raise worker pay was higher. At the same time it is taking longer than ever to fill vacancies while there is barely 1 unemployed person for every job opening being created.

Given the US is predominantly a service sector economy and wages are the dominant cost input to such a business, these developments suggest inflation pressures will continue to build – even after taking into account productivity improvements. After all, in an environment of such strong demand, corporates have the pricing power to pass on higher costs. At the same time, rising commodity prices and a weaker dollar are adding to pipeline price pressures while housing and medical care costs are on the increase.

The unwinding of distortions relating to cell-phone data plans will add 0.2-0.3 percentage points by April and the gradual erosion of slack in the economy will also nudge up inflation pressures. As such, we still believe that headline consumer price inflation could hit 3% in the summer.

At the moment the Federal Reserve is projecting that it will raise rates three times this year, with financial markets currently pricing in around 80bp of Fed rate hikes by December. We have decided to insert a fourth 25bp move into our own forecasts given the risk of a damaging government shutdown has been pushed out into the long grass following the recent budget deal agreed by Congress. We are now forecasting one rate hike per quarter.

The Treasury market has responded to this strong growth, higher inflation risk environment with the 10Y yield pushing close to 3%. We believe it will soon break above and could potentially touch 3.5%, given our view that the market is a little too relaxed about the path for inflation and Fed policy (remember the Fed is also shrinking its balance sheet). Should worries regarding the fiscal deficit intensify, the risk to yields will be increasingly to the upside .

James Knightley, London +44 20 7767 6614

Eurozone: Hitting top speed

In his statement to the Economic Committee of the European Parliament, Mario Draghi summed it up nicely: all of the monetary policy measures taken between mid-2014 and October 2017 will have an estimated overall impact on euro area growth and inflation, in both cases, of around 1.9 percentage points cumulatively for the period between 2016 and 2020. However, the evolution of inflation remains crucially conditional on an ample degree of monetary stimulus provided by the full set of the ECB’s monetary policy measures. In other words: growth is there, but inflation remains a work in progress.

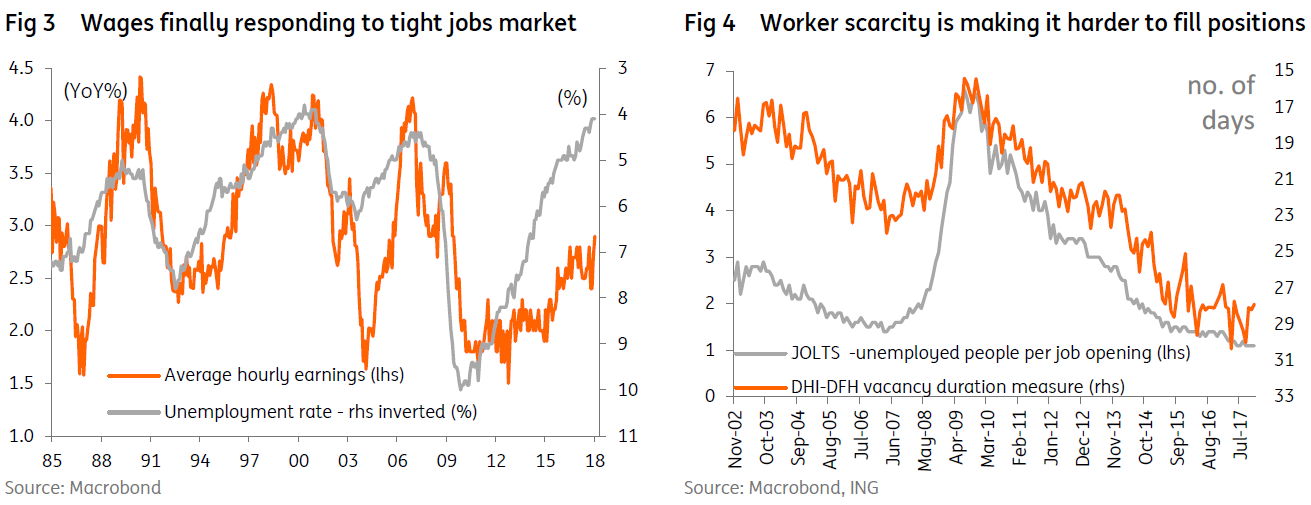

While we certainly don’t want to become bearish on the growth outlook, recent data seem to suggest that the acceleration in growth might soon start to level off. As we pointed out before, sooner or later, the strong euro had to have some impact. And that is precisely what the February German Ifo-indicator is telling us. While the “current conditions” component remained close to an all-time high, suggesting a strong first quarter, business expectations came out a lot weaker, probably penciling in the future adverse impact of the strong euro on exports. It was the same story in the Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI). The slower growth of business activity reflected an easing in the rate of increase of new orders which fell to a five-month low.

That said, underlying growth still seems strong enough, as companies boosted their staffing levels to one of the greatest extents seen over the past 17 years. February’s €- coin indicator even suggests an annualised GDP growth pace of close to 4.0% in the first quarter! Admittedly, consumer confidence weakened in February, but that was probably due to the financial market turmoil in the period the survey was taken. With the annual growth rate of adjusted loans to non-financial corporations increasing to 3.4% in January, from 3.1% in December, the capital expenditure outlook also looks good. So, all in all, we remain comfortable with our GDP growth forecast of 2.4% this year, though we believe that the growth pace will slow a bit, albeit stay above potential, in the second half of the year.

While the political uncertainty in a number of European countries might still last a bit longer (eg, it is likely going to take some time to form an Italian government), we don’t think that this will derail the recovery, though it could force the ECB to tread carefully in its exit strategy.

The first German wage agreements came out at the high side of expectations, but they are unlikely to boost inflation significantly, since more flexibility and productivity gains should temper the impact on prices. That said, at the current stage in the recovery, downward pressure on real wages is ebbing away in most European countries. At the same time, there is still some slack in the labour market, as average hours worked are still lower than before the crisis. So the view of a slow pick-up in inflation is still valid, though we don’t think that underlying inflation will top 1.5% this year.

From the minutes of the last meeting of the ECB Governing Council we know that a number of members asked for the removal of the easing bias in the statement. However, the majority rejected this suggestion as it still seems premature. Indeed, already announcing an end to quantitative easing (QE) now, would most probably lead to a further strengthening of the euro and an increase in bond yields. This would then delay the return of inflation towards its target. Therefore, we believe the ECB will keep its cards close to its chest and wait as long as possible before making any announcement on the continuation or the end of the asset purchase programme.

We stand by our expectations of an extension of the ECB’s net purchases until the end of the year and a first 10bp deposit rate hike in June 2019. Bond yields, which saw a rapid rise earlier in the year, are now consolidating. While we believe that the underlying trend is still upwards, we see bond yields moving sideways over the coming months.

Peter Vanden Houte, Brussels +32 2 547 8009

UK: Some Brexit clarity at last?

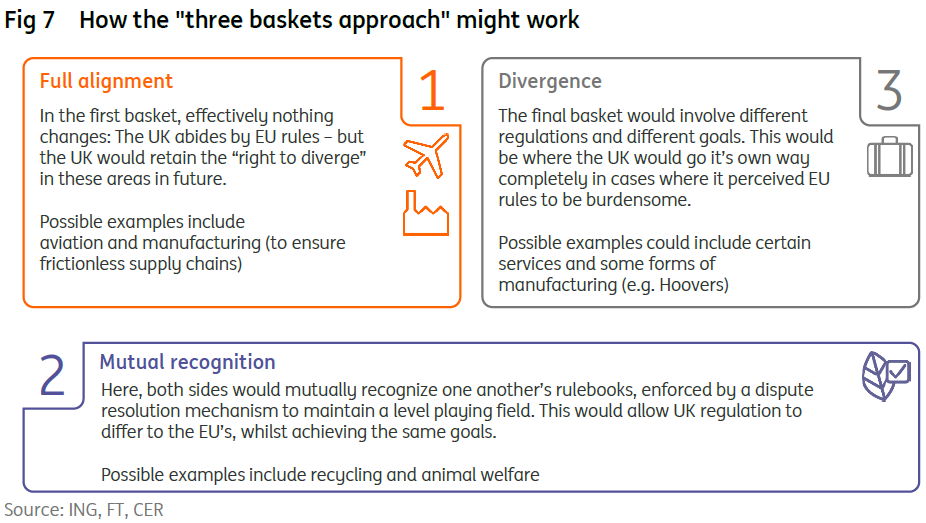

For several months now, key ministers in the UK government have been heavily divided on the way forward on Brexit. But after a marathon eight-hour “Brexit away day”, Prime Minister Theresa May has reportedly agreed on a compromise which can unite the key factions within the cabinet. The compromise reportedly goes by the name of “managed divergence” (or “Canada plus plus plus”). At the time of writing, we are awaiting a speech from PM May on the full details, but it's assumed that this model would involve dissecting different areas of economic activity into three baskets:

The beauty of this, in theory, is that there’s something for everyone. “Remain” ministers would be happy because it would allow the UK to remain closely aligned to the EU in key areas. And for the “Brexiteers”, it allows the government to “take back control” of regulation where it perceives EU rules to be burdensome.

Of course, it’s one thing getting UK ministers on board. Getting the EU to agree to such a proposal looks much more challenging, and in fact the European Commission published a slide last week saying it is “not compatible” with its guidelines.

From the EU’s perspective, the managed divergence proposal sounds a lot like ‘cherry picking’ – a key red line for European governments, who are strongly opposed to allowing the single market to become divided up.

There are also reportedly fears that it could result in a backlash from the EU’s other key trading partners. A deal that enables the UK to excel after Brexit could embolden members of the EEA to request concessions of their own, or even make EU exit seem more appealing to some of the more eurosceptic existing member states. European negotiators will also be acutely aware that whatever both sides agree on services would also have to be offered to existing free trade partners (eg, Canada and South Korea) under most-favoured-nation clauses.

There are practical considerations, too. Reconciling the differing views of the 28 countries involved in the negotiations on exactly what sectors/areas would sit in each basket would be a very complex and time-consuming task.

But perhaps the biggest issue is that the "three baskets" approach is unlikely to mitigate concerns over a hard border with Ireland. As part of the phase I agreement back in December, the UK agreed that there would be "no regulatory divergence" between Ireland and the North. The UK's government's decision to leave the customs union, and preference to move away from certain EU rules after Brexit may not be enough to meet December's commitment.

Of course, none of these EU red lines are particularly new. But it is possible the UK government is banking on divisions amongst member states coming to the fore. Behind the scenes, some European governments are reportedly becoming frustrated with the more rigid approach taken by Michel Barnier and the European Commission, favouring instead a more pragmatic/flexible approach. Further down the road, we may also see the UK float the possibility of some post-Brexit budgetary contributions, or a more liberal EU migration policy, in a bid to win concessions on trade from Europe.

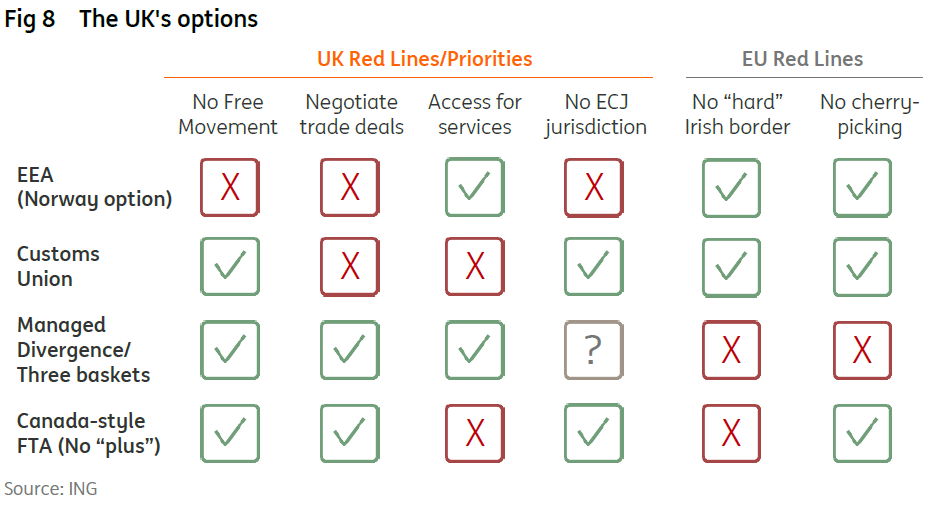

Assuming though that the EU does reject the UK's proposal, this effectively leaves the government with three options. The first is the EEA, although this would involve freedom of movement, perhaps the reddest of red lines for the UK government. The second - and perhaps most likely outcome given the UK's red lines - is a Canada-style free trade agreement (although possibly with limited access to services). The third option is joining a customs union in goods with the EU.

So far, this has been strongly ruled out by UK ministers because it would prevent the government from pursuing trade deals with non-EU countries. It would also likely require the UK accepting EU regulations on goods. But the issue has come sharply into focus now that the opposition Labour Party has confirmed it favours the customs union option. There are also reportedly a number of Conservative MPs who also agree with the Labour stance, some of whom have proposed amendments to the government's trade legislation that would commit to joining a customs union after Brexit.

A vote on these amendments in the House of Commons has reportedly been pushed back by as much as two months, but given the government's working majority in Parliament is just 13 MPs (out of 650), the outcome would be very tight. As the FT noted this week, a defeat on this issue could be a major blow to Theresa May's leadership.

The EU has also raised the stakes by requesting Northern Ireland remain in a customs union as a "fallback option", should the overall Brexit deal fail to address hard border concerns. Theresa May has since said "no UK Prime Minister could ever agree" to this, not least because it would likely raise serious concerns within the Democratic Unionist Party (the DUP) over barriers to trade within the UK itself. Of course, nothing is agreed until everything is agreed, so it may not be until right at the last minute before a deal is struck. But until then, this issue is only likely to keep pressure on the government to compromise on some of its red lines, including customs union membership.

James Smith, London +44 20 7767 1038

China: Stability guaranteed

President Xi Jinping’s tenure will be extended. What does this mean for the economy?

Although Xi’s tenure will no longer be limited by the constitution, it will end at some point. Let’s assume that the arrangement would be similar to a Kingdom. Whether the Monarch eventually abdicates or passes away, the monarchy passes to someone else. The same arrangement is likely to apply to Xi, who is now 64. That means he could be the country’s leader for a very long time.

Overall, this is positive for the economy because economic policies are likely to be consistent. In contrast, democratic countries’ policies often get overturned at elections, and fail to achieve their goals. China does not have such hindrances. So Xi can set his policies with a long-term vision.

Xi has already initiated several important projects for the economy. These need time for the results to be seen. Firstly, the anti-corruption campaign. Secondly, the Belt and Road Initiative. And finally, to modernise society, that is, to have a society that is wealthy and high-tech. With Xi likely to be in place for a long time, there is a higher probability that these projects will conclude and achieve their results, and in turn, provide economic stability.

To maximise the benefit of Xi’s longer tenure, Xi will also need his advisory team to be as stable as possible. That means he will engage people who share his thoughts (Xi’s new era thoughts), which will be added to the State Constitution after they have been added to the Party’s Charter.

As the economy becomes stronger and more stable, other countries will start to feel that the rise of China could provide opportunities as well as risks.

Japan and Australia have gestured that they would like to create another project similar to the Belt and Road initiative (BRI). This is perhaps because these two economies are left out of BRI. In the meantime, western countries see China’s strength as more of a threat than an opportunity, with the US and some European countries hinting at trade sanctions against China’s products.

Could this turn into a trade war? We do not think so, because we do not believe that China will react by imposing retaliatory trade sanctions on other countries. This includes the US despite its intention to slap import tariffs on steel and aluminium. We doubt China will react with tariffs on US food imports. There is a more effective way for China to prevent countries ratcheting up their trade sanctions against them. For one, China could simply stop the companies of hostile countries from operating in Mainland China. Companies of hostile countries would lobby their governments in turn.

Besides running a stronger economy, Xi may build up China’s military power faster as mentioned in the 19th Congress. Neighbouring countries and the US will feel the heat. But it is too early to say whether China’s military power will worsen geopolitical tension.

The Two Sessions, Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) and the National People’s Congress (NPC), will be held on 3 and 5 March. We expect by then, Xi’s advisory team will be clearer and we should know who will lead the central bank (PBoC) as Zhou retires for another role.

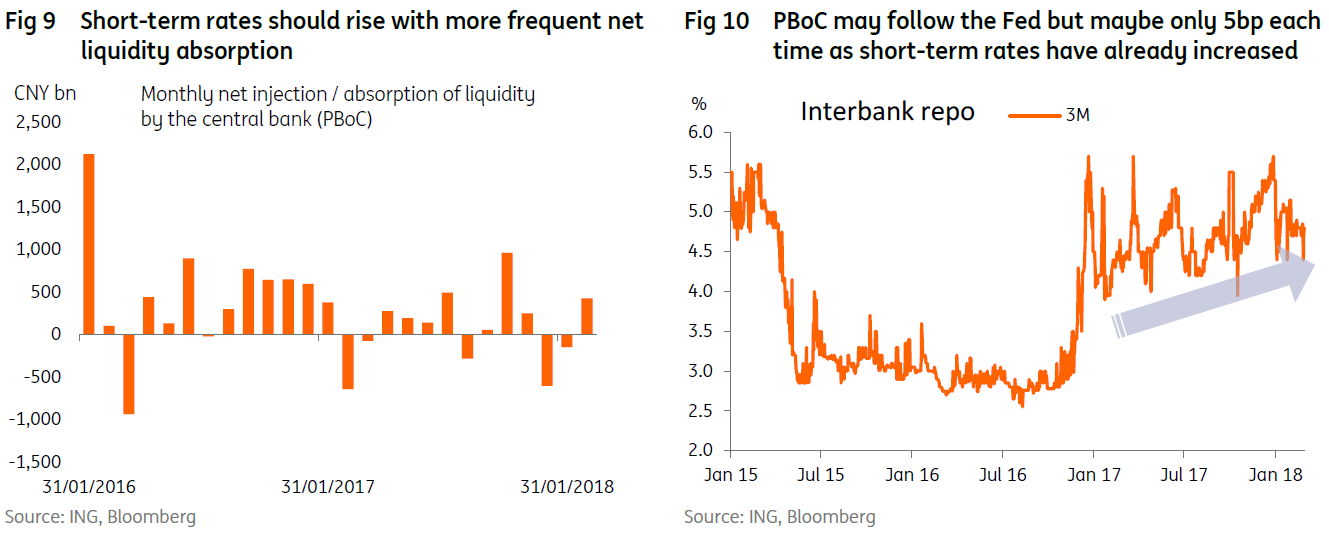

We believe that the new central bank governor will be someone who shares Xi’s gradual reform approach on interest rate and exchange rate liberalisation. That means the status-quo for monetary policy and exchange rate policy. We believe the central bank (PBoC) will follow the Fed’s four expected rate hikes in 2018 to keep interest rate spreads stable, but could only add five basis points each time, as financial deleveraging would push up short term interest rates further. The exchange rate mechansim will also remain largely the same. We do not expect any widening of the daily trading band unless the spot rate becomes more volatile during intraday sessions. We maintain our forecast of USD/CNY and USD/CNH of 6.1 by the end of 2018.

Japan: Something fishy

Japan’s inflation emerged from negative rates in September 2016, and is now comfortably above 1% (1.4% headline). With a 2ppt consumption tax due in April 2019, the next 18-months to two years offers to be one of unexpectedly robust inflation for Japan. So is it time for the Bank of Japan (BOJ) to ditch their Qualitative and Quantitative easing (QQE)?

The answer to this partly depends on why inflation is rising and what else is happening in the economy.

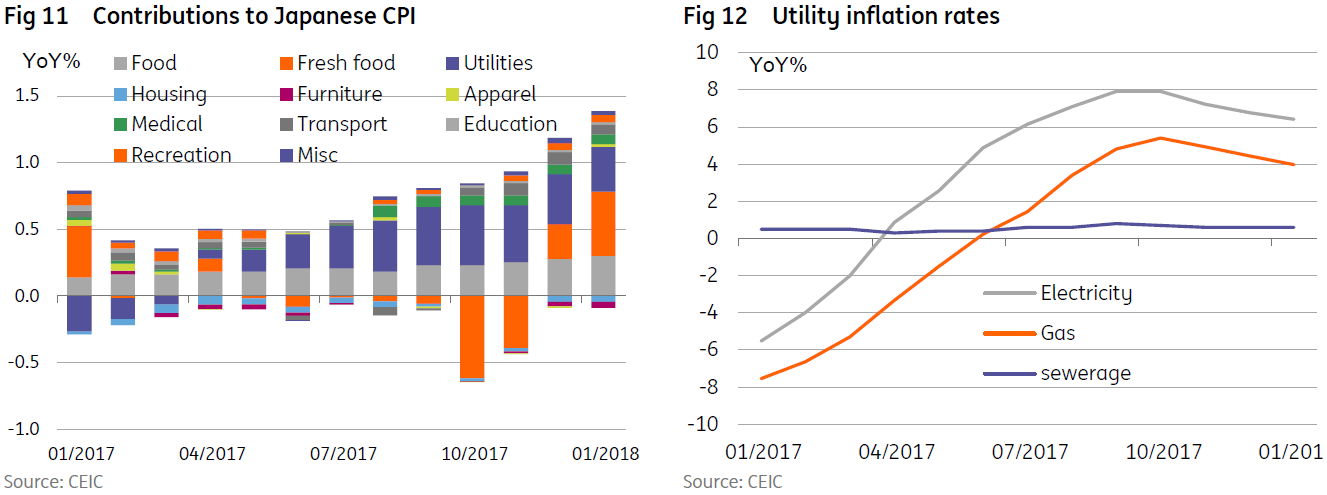

On the former, there are two main factors to consider. The first is food. Normally we would exclude this, as volatile fresh food prices can dominate the headline index. But non-fresh food has also risen, and that is harder to just write off.

What appears to be going on is a combination of fish, and gas. The Seafood component of Japan’s CPI is large and highly diverse. But within this, there have been some substantial price spikes for fish such as tuna, bonito and saury, A spillover of the rise in the prices of fresh fish is that products such as dried fish, squid or salted fish-guts (yes, there is a category for this) have pushed substantially higher. And as the key ingredient for sushi and sashimi, prices of Japan’s iconic prepared dishes have been soaring.

The root cause of these price spikes is essentially supply. Fish catches have been very disappointing. For some fish, catches are less than half of last years, which were also historically low. This looks like an overfishing issue, with fish stocks collapsing. Consequently, the collapse in supply is unlikely to reverse quickly and may require years of fishing restraint to help rebuild stocks. This too will keep prices high, or perhaps lead to further rises.

The other main cause of inflation is gas. After the Fukushima earthquake and destruction of Japan’s nuclear power generation, Japan became heavily reliant on LNG imports. Wholesale gas prices for purchase in Japan are not particularly high, but they have bounced off their lows of 2016/17 as LNG is also a popular fuel for other countries these days, as cleaner sources of power are sought against a backdrop of relatively inelastic supply. This is pushing up prices of retail gas, but other fuels such as electricity.

Both of these issues are essentially “supply shocks”, arising from (1) a lack of fish and (2) a lack of global LNG relative to demand, and not necessarily something the BoJ would respond to.

But the growth data is also good, and the arguments for keeping QQE unchanged are looking thinly stretched. This week, the BoJ cut the amounts of super-long dated bonds it usually buys, and we are beginning to wonder if, in the global backdrop of rising rates and bond yields, the BoJ is wondering how it can create an exit strategy that will not result in a USDJPY rate smashing through 100. We haven’t raised our forecast for JGB yields, though we have trimmed our “actual” asset purchasing by the BoJ from JPY45tr in 2018 to JPY30tr (official target is still JPY80tr annually). Nevertheless, this is something we shall be thinking hard about over the coming months. The days when you could just forecast zero for everything forever in Japan seem to have passed.

Rob Carnell Chief Economist, Asia Pacific +65 6232 6020

FX: Consensus slowly adjusts

Investors are still trying to determine the key FX themes of the year. The conviction call remains that the world economy will grow, but the jury is out on whether (US) late-cycle inflation will be enough to tip over the investment environment and favour defensive FX strategies. Irrespective of the investment environment our conviction call is that the dollar is in a multi-year decline – a view to which consensus is only slowly adjusting.

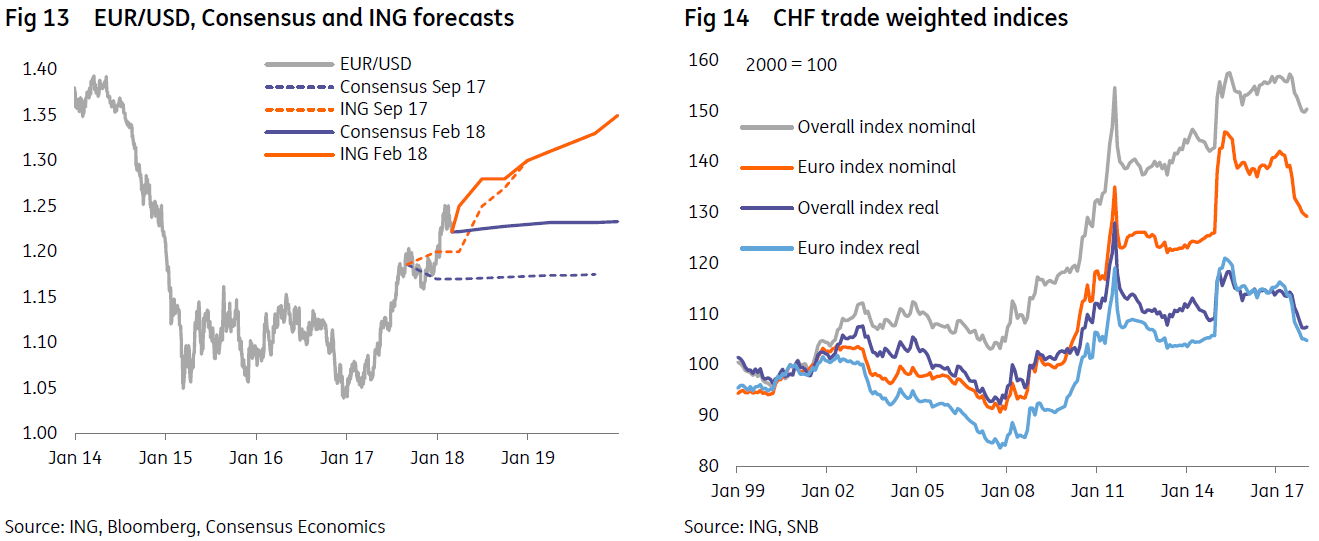

Consensus (98 instititions surveyed by Consensus Economics) now expects EUR/USD to end 2018 near 1.23 and end 2019 near 1.24. As can be seen from the chart below, consensus forecasts have recently struggled to price in significant deviations from current spot prices. The reality is that major FX pairs rarely trade in straight lines and instead it is important to build an early understandinng of emerging narratives.

As we highlighted last month, we are seeing early signs of a new, negative dollar narrative develop – one that questions the ability of the US to fund its growing deficits at the same cost, be that cost Treasury yields or the exchange rate. This month’s escalation in US protectionism very much re-affirms this theme.

Our view is that Trump’s pro-cyclical fiscal policy is storing up problems for the dollar in 2019/20. Rather than waiting for the bad news in 2019, however, we think investors are starting to price that bad news into the dollar today. The ECB’s Benoit Couere touched on this theme in a speech in November when he highlighted that ‘international portfolio rebalancing considerations may, at times, drive a wedge between expected future short term rates and the exchange rate’.

We remain comfortable with EUR/USD forecasts at 1.30 and 1.35 for end year 2018 and 2019 respectively. While the ECB may not like this, the substantial Eurozone current account surplus of 3.5% of GDP provides nowhere for the ECB to hide. And any US Treasury lip-service to a strong dollar policy at the next G20 Finance Ministers meeting on 19 March is unlikely to give the dollar lasting support.

FX markets also have some European political risk with which to contend in the form of Italian elections and the SPD vote on the German coalition. These fears have yet to show up in bond markets, although higher volatility this year has lifted the CHF.

With policy rates at -0.75% and continued intervention in FX markets, the Swiss National Bank (SNB) remains in ultra-dovish mode. No doubt it welcomes the depreciation in the CHF trade weighted exchange rate seen last year – but still wants more. We have a very non-consensus view on EUR/CHF that the ECB’s move to adjust policy – and the SNB remaining dovish far longer than the ECB – can drive EUR/CHF to 1.25.

Chris Turner, London +44 20 7767 1610

Rates: Breach of 3% ahead

Since the banking crisis of 2007/08 we’ve been remarking on how low US rates have been versus average. For the first time since the banking crisis broke, we now find that rates in the 3yr and 4yr tenors are back to their 15yr average. Some of this of course reflects ‘slow grind’ falls in the 15yr average reflecting quantitative easing and the years where the funds rate was at zero (to 25bp). That said, the move back to average is worthy of note.

It is also important to contrast the convergence to average for 3yr and 4yr tenors with the fact that the 10yr is still some 60bp below the 15yr average and the 30yr is 120bp below. This in turn points to the vulnerable areas of the curve. The front end is facing into expected Fed hikes and will ratchet up to reflect this as they are delivered. The bigger debate is on longer rates, and the answer will come from the inflation outlook.

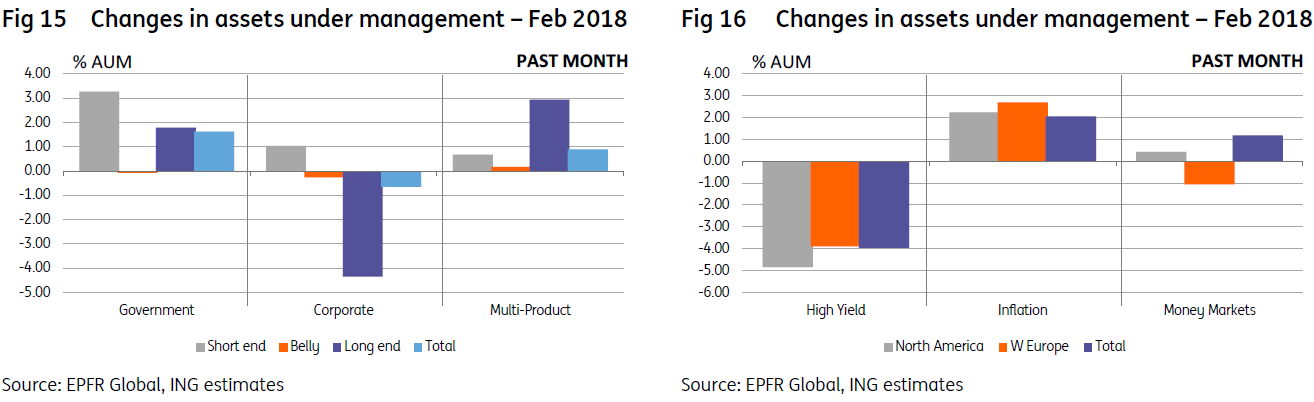

Energy effects will likely push the headline rate towards 3% in the coming quarters, from where it should then drift back down to meet the core with should land in the 2.2% area. The headline move will raise eyebrows, but the core move is key. Both will test resilience in long rates. The threat of a rising fiscal deficit ahead presents an additional headwind.

We note that there has been some buying of long end funds in the past month, reversing some of the duration short that was set through January. Hence the failure of to break above 3%, indeed the drift back (briefly) to 3.8%. We’d fade these tests lower in yield, as the structural theme remains in line with a test higher.

Bottom line, we are not convinced that the rise in market rates is behind us, and we identify continued vulnerabilities in the belly of the curve (5yr to 10yr). At some point in the coming months we anticipate an attack on 3% for the 10yr, and our models suggest that the 3.25% area is a minimum threshold to be achieved bond longs are considered.

Euro rates have been dragged higher by US rates, and with the front end anchored by ECB policy, the curve has stretched further steeper – the biggest of the rise in rates has been in the 7yr to 10yr area. The big contrast with the US is that Euro rates are still some 200bp below the 15yr average.

The latter is a point of vulnerability, as at some point in the coming few quarters that gap (current vs mean and Euro vs US) should begin to close in a precipitous manner. Perhaps not something that is imminent, but certainly a theme to be positioned for as we progress through 2018, as it will almost certainly be upon us in 2019, as the ECB hikes the deposit rate first and then the refi rate.

Padhraic Garvey, London +44 20 7767 8057