1, 2, 3 Boom!

Evidence of a broadening and more global growth story is increasingly powerful. The US looks set to hit 3% growth this year, and the European and Japanese figures are looking more robust. Emerging markets are also strengthening, with Latin America finally joining the party after recent struggles. The consensus forecasts are rising too, but we believe that they are still too pessimistic. Rising asset valuations are a potential threat, but with growth looking so strong and so much cash on the sidelines, any near-term correction is likely to be shallow.

The US remains at the forefront of this story with the prospect of 3% growth, inflation and 10Y Treasury yields this year. 4Q17 GDP data showed how much momentum there is in the domestic economy and President Trump’s tax plan provides more fuel for this year and next. At the same time, the dollar’s ongoing weakness means the US is in a very competitive position to take advantage of the global upturn in demand.

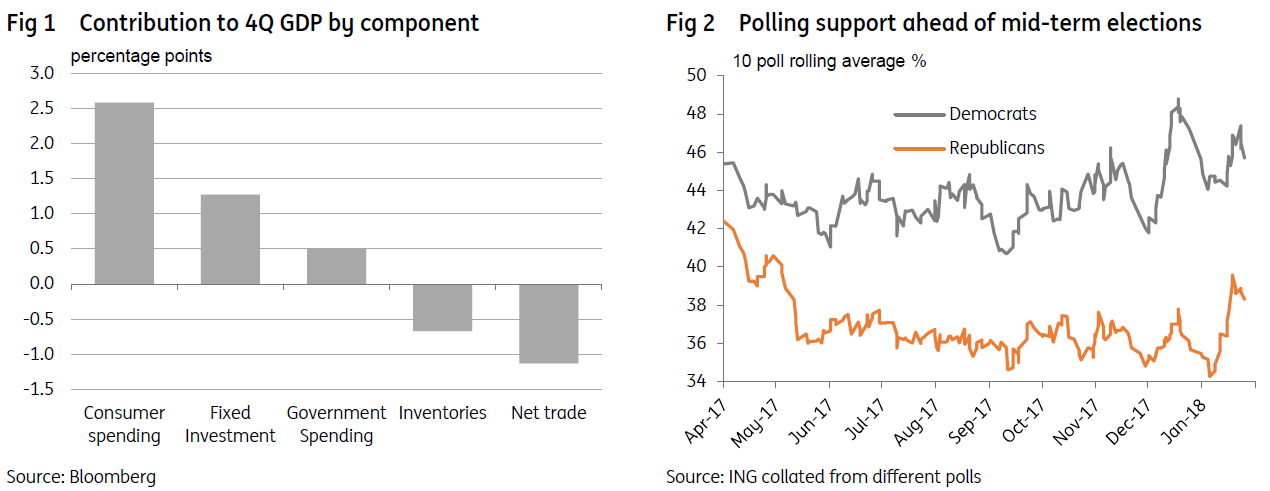

Another support for GDP growth could come in the form of infrastructure spending, which got a renewed push in President Trump’s State of the Union Address. Through a mixture of public and private funding he is looking to implement US$1.5 trillion of upgrades and new work. But given that the Republicans are lagging well behind Democrats in polls for November’s mid-term elections, time of is of the essence to get legislation passed.

After having recorded the strongest growth in 10 years in 2017, the Eurozone saw the good run of data continue in January. However, inflation remains subdued and the rapid strengthening of the euro is another reason for the European Central Bank (ECB) to tread carefully when removing monetary stimulus. An interest rate hike this year still seems highly unlikely.

The UK has also provided some positive surprises, but ‘Brexit’ means that there are still huge uncertainties. We believe there is a narrow window for a rate rise, most probably in May, but this depends on ongoing wage improvements and progress on Brexit talks. As such we think it is a 50:50 call.

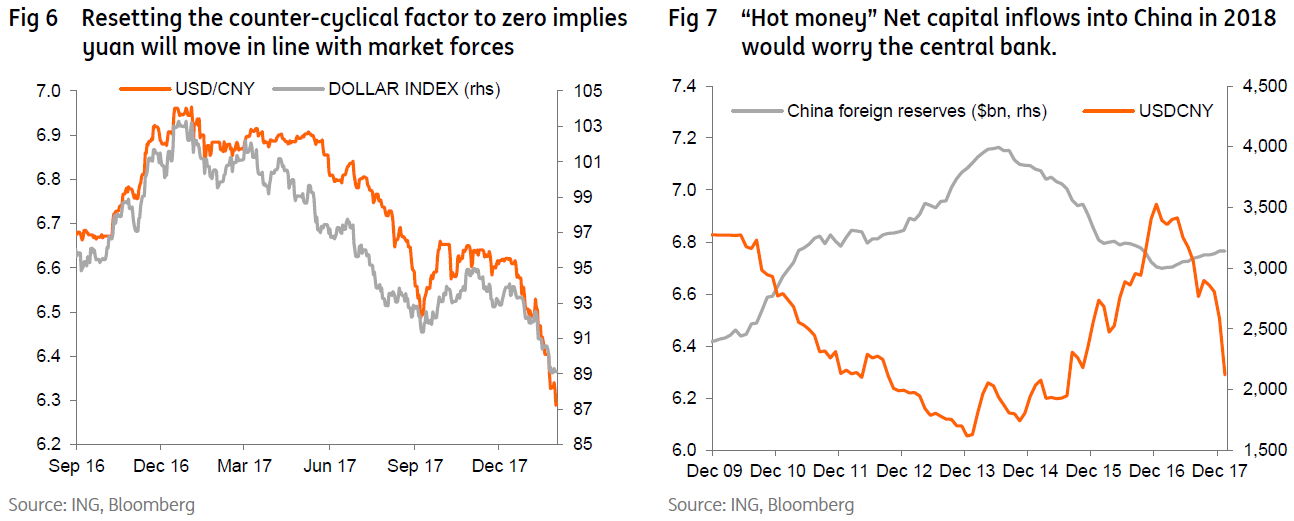

The Chinese government prefers to keep the yuan following market forces to avoid the false impression of creating a currency war. But with a wider interest rate spread and yuan appreciation, there could be hot money inflows in 2018. We have revised our forecast of USD/CNY to 6.10 by the end of 2018.

Japan’s strong growth continues, though the unbroken record of GDP gains looks vulnerable. Despite the prospects for a temporary blip in the GDP numbers, the underlying growth story has strong corporate profit underpinnings. PM Abe is piling pressure on the corporate sector to pass on some of these profits to workers as wages. Meanwhile, the Bank of Japan (BOJ) is sticking to its guns in denying any imminent end to quantitative easing . We suspect they will eventually cave in to market pressure and the macro reality later this year, but will try to minimise the market impact of any changes to policy.

US protectionism and a mercantilist dollar policy have emerged as a key FX theme over the last month. We cannot see this story changing much in advance of US mid-term elections in November. We have accordingly cut our year-end USD/JPY forecast to 100.

US: Three – the magic number…

Bob Dorough and De La Soul both agreed that three is the magic number and it also neatly sums up our economic and market forecasts for the US this year. We are looking at an economy that is growing 3%, that could see inflation hit 3% in the summer, which will trigger at least three Fed rate hikes and nudge the 10Y Treasury yield up to 3%.

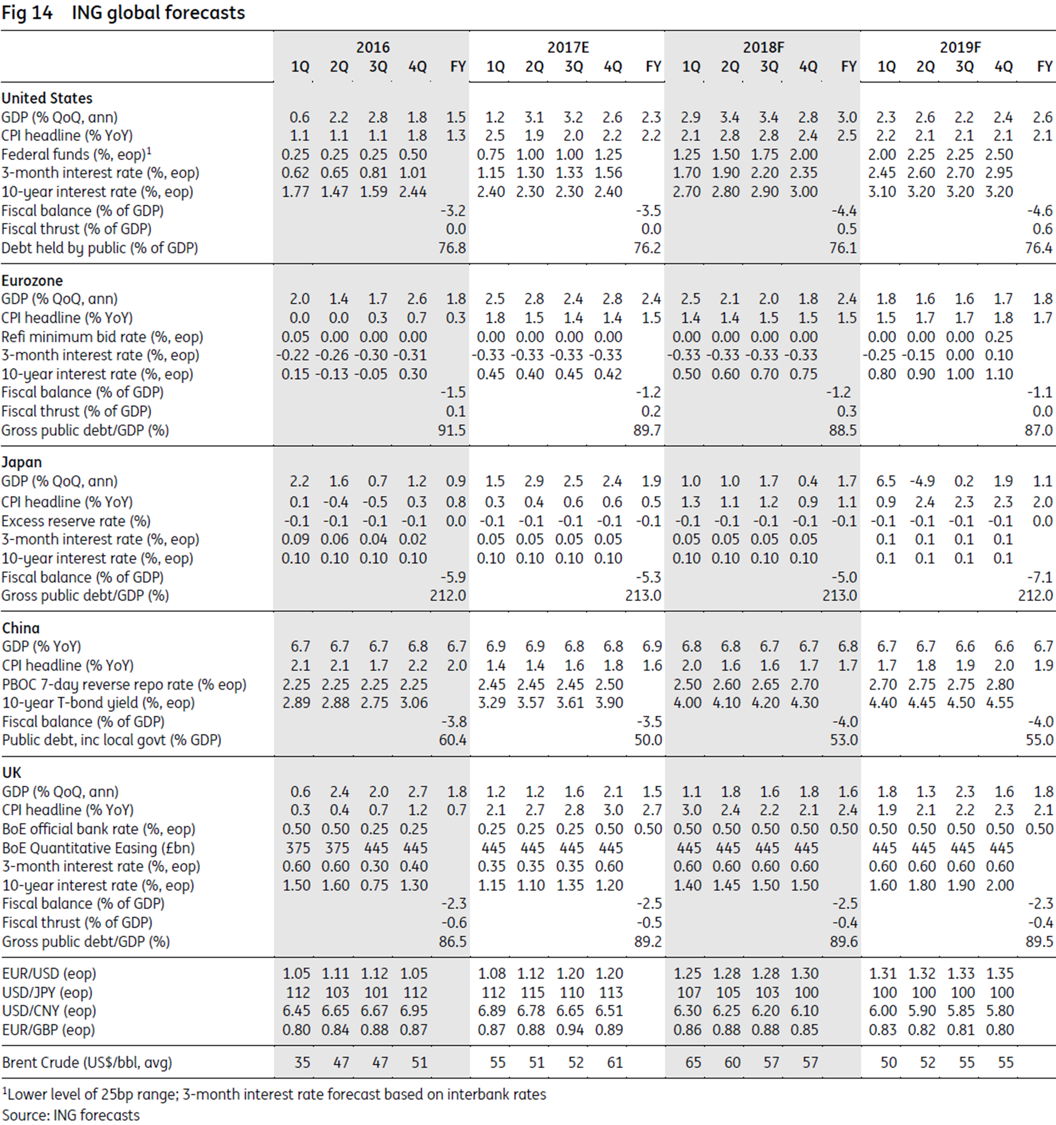

The US economy continues to perform very strongly with confidence and stock markets at record highs, unemployment at 17 year lows and domestic demand looking very robust. This was in evidence in the 4Q GDP report where consumer spending, investment and government spending all grew at 3% or more annualised rates.

December’s tax reforms should provide a boost for this year by putting more money in the pockets of households while the corporate sector has responded positively with several announcements on investment projects and the boosting of worker pay. Nonetheless, we still suspect the majority of the windfall for corporates will be spent on share buy-backs and special dividends, which will provide support for equity prices.

Net trade was a weak spot in the 4Q GDP figure, with imports of goods rising 16.8% annualised. Exports didn’t grow anywhere near as quickly, meaning that trade itself subtracted 1.1 percentage points from headline GDP growth. Interestingly, this wasn’t jumped on by President Trump as another reason why the US needs to adopt more protectionist policies. Earlier in the week new tariffs had been placed on imports of solar panels and washing machines, but by the end of the week Donald Trump was striking a friendlier tone in his speech at the World Economic Forum in Davos.

In fact, we think that the US is in a great position to benefit from the upturn in global demand given dollar softness has improved international competitiveness. It appears that Trump is becoming more accepting of free trade so long as it becomes “fairer” and is “reciprocal”. This suggests to us that NAFTA won’t be imminently ripped up. If anything the more likely scenario is that talks drag on until late 2018 after the US midterm elections, Canadian provincial elections and the Mexican Presidential election.

Inventories were also a weak spot, subtracting a further 0.7 percentage points from headline growth, but as with net trade we expect to see better numbers in coming quarters. It was likely to have been an involuntary run-down and could be the prelude to some very strong manufacturing numbers as businesses look to replenish stock levels.

As for inflation, core CPI has picked up to 1.8%YoY and we see it rising further in the next few months. The unwinding of distortions relating to cell-phone data plans will add 0.2- 0.3 percentage points by April and the gradual erosion of slack in the economy will also nudge up inflation pressures. Add on lagged effects of dollar weakness and the ongoing increases in energy costs and we think that we could be looking at headline CPI touching 3% this summer.

In this environment we believe the Federal Reserve will carry through with its own projections of three interest rate hikes. However, we are in a minority currently forecasting no hike in 1Q18. Admittedly this is a low conviction call, but we certainly think that the prospect of a rate hike in March is not as cut and dried as market pricing suggests – the implied probability is currently around 90%.

Our reasoning is the forthcoming handover at the Fed – March will be Jerome Powell’s first FOMC meeting as Fed Chair, while core inflation is unlikely to be above 2% before the 21 March FOMC meeting. We also see some risk to softer activity numbers in January given the bad weather at the start of the year while the potential for another, more serious government shutdown continues to linger. However, should these risks subside we will likely have to put a March hike in our forecasts – potentially as a fourth hike rather than just shifting forward the three 2018 moves we are currently predicting.

This year will also be a big year for politics and President Trump laid out his plans at the State of the Union Address. Infrastructure spending is the big policy push for 2018, along with tighter border controls. However, his poll ratings remain poor and he may need to move quickly given the potential for the Republicans to lose their majority in the House of Representatives after the mid-term elections. The latest polls show that despite a post-tax reform bounce they are the best part of eight points behind the Democrats. Trump will be hoping the magic of 3% growth can still deliver him victory.

James Knightley, London +44 20 7767 6614

Eurozone: growth party with euro

headache

With 2.5% GDP growth in 2017 the Eurozone economy recorded the strongest expansion in 10 years. On top of that 2018 saw a strong start, with the composite PMI surging to its highest level in 12 years in January. While real activity does not necessarily match sentiment indicators (the PMI suggests 1% non-annualized GDP growth), there is no denying that the current batch of economic data signal above potential growth.

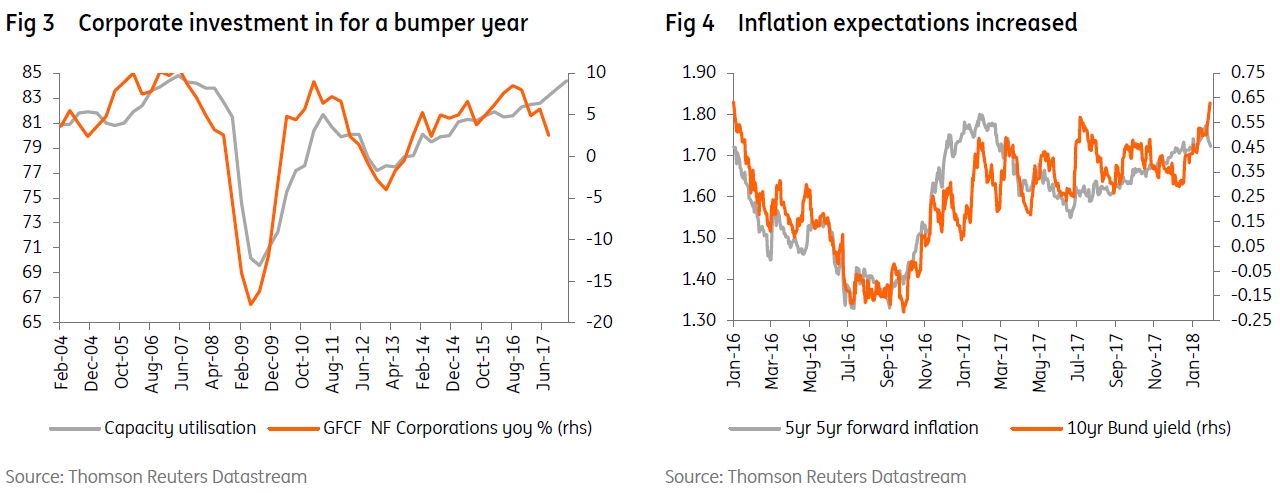

Whereas last year consumption growth remained below the overall growth rate, we expect household expenditure to be a strong growth driver this year. Indeed, the assessment of the labour market is at the strongest level since the year 2000. Higher employment, gradually rising wages and a declining savings rate should boost consumer spending this year. At the same time, investment and construction look to be in for another bumper year.

However, the markets’ attention is now shifting towards the strength of the euro exchange rate. Since the beginning of November the euro has gained more than 7% against the dollar. While it is too soon to detect an impact on growth or inflation, one shouldn’t completely downplay the potential harm of a sudden currency appreciation, even when the strengthening is based on an improving economy. Export volume expectations in the manufacturing sector, though staying at a high level, declined slightly in January, while the assessment of the competitive position also diminished marginally. If sustained, euro strength will probably cause a gradual growth deceleration in the second half of the year.

For the ECB the strength of the euro complicates the outlook for monetary policy. A number of reports are signalling rising pipeline inflation. And markets have been scaling up their long-term inflation expectations. On the other hand, a stronger currency and a stabilisation or slight decline in oil prices point into the opposite direction. According to the bank’s models, a 1% effective appreciation of the euro results in a 0.1ppt lower HICP inflation rate after 1 year. Headline inflation in January came out at 1.3%, while core inflation was 1.0%, still significantly below the ECB’s objective.

In that regard the dovish statements of the ECB’s chief economist Peter Praet look important: “Even if incoming data were to validate the expectation of a gradual build-up of inflationary pressures, this would not be sufficient to affirm a sustained adjustment, if even less supportive monetary policy conditions were to imperil the inflation trajectory”. While a number of central bank governors have recently pleaded for a timely end to the quantitative easing programme, there still seems to be consensus to have a short taper after September.

This means that we maintain our scenario of an end to the QE programme in December and a first deposit rate hike by the summer of 2019. While we think that a gradual increase in bond yields looks likely in that regard, it would be not abnormal to see the recent abrupt rise in bond yields partially reversed, before heading higher again.

On the political front, the Italian political landscape continues to shift in the run-up to the March elections. The departure of the 5 Star Movement’s founder, Beppe Grillo, opens up the possibility of coalitions with other populist parties like Lega Nord. This is a risk, as Lega Nord is against the euro, but we don’t believe that such a coalition would be able to clinch a majority. That said, the fragmentation of Italian politics is likely to result in weak governments. While this may not upset markets in the short run it could become a problem when the next downturn arrives.

Meanwhile, we are also nearing the end of the third Greek program, meaning that Greece will have to stand on its own feet from 20 August onwards. The government very much hopes for a “clean exit” like Ireland and Portugal, but with Greek bonds still rated as junk (and therefore not eligible anymore as collateral at the ECB if Greece is no longer in a program), some form of assistance, like a precautionary credit line, still looks needed. That could be this year’s summer story.

Peter Vanden Houte, Brussels +32 2 547 8009

UK: The narrowing rate hike window

As we noted last month, there are plenty of tough decisions to be made in the UK in 2018. One of these decisions lies with the Bank of England, which must choose whether or not the economy can handle further rate hikes. Policymakers have loosely signalled they would be prepared to increase rates at some point again this year, and amongst other things, the decision hinges on wage growth and Brexit.

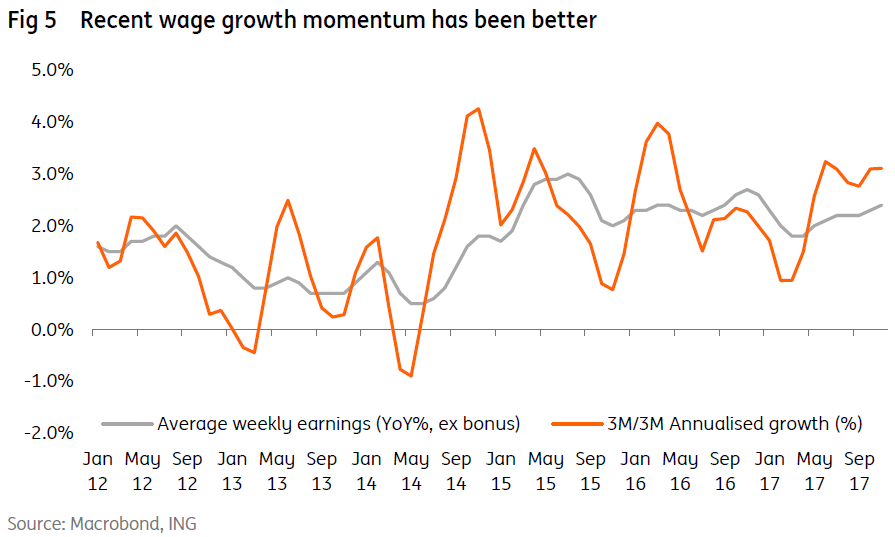

On the former, there’s little doubt the latest news has been more positive. For instance, take a look at the 3M/3M annualized growth in wages (which whilst clunky-sounding, is a better measure of current momentum than year-on-year comparisons). This suggests pay is rising has been rising at an annualized rate of 3% over the past 3 or 4 months.

What’s less obvious is why wages have been rising more quickly of late, or how long it will last for. The upbeat explanation, and the one backed by the Bank of England, is that firms are having to increasingly hike salaries in a bid to retain staff. With the unemployment rate at the lowest level since 1975, there are signs that skills shortages are developing certain sectors. There have also been suggestions that some employers are feeling pressure to ensure wages keep pace with the cost of living, with inflation currently close to 3%.

This is all likely to be true, but there are a few reasons to treat the recent momentum with an element of caution. Some of the pick-up witnessed over recent months is linked to an increased minimum wage. It’s worth noting too that the latest rise comes off a very low base – the level of pay was virtually flat through last winter.

We also suspect that some firms will continue to take a more conservative wage setting approach, particularly amidst low productivity growth, sluggish economic growth and rising input costs, all of which will be putting pressure on margins. We’re therefore still slightly sceptical that wage growth will rise dramatically as the Bank of England expects – 3% on average in 2018.

Having said that, we suspect the recent momentum may give the majority of MPC members more confidence that the direction of travel is positive. It’s also worth noting that the headline wage growth figures will be flattered by the base effects that we noted above (a weak start to 2017) over the next few readings. Put another way, there’s little reason at this stage for the Bank to doubt its optimistic outlook for pay – although we suspect they may look to nudge down their 3% forecast a touch at the February meeting.

So with a tick provisionally in the wage growth box, the odds of a rate hike this year look increasingly dependent on Brexit. The BoE bought itself some time in December by saying that it would provide a fuller analysis of Brexit progress at the February meeting. But since it said that, there’s been little to report. Nothing has been firmly agreed on the transition period, while technical talks on the finer legal issues continue. Nor has there been any further clarity on which Brexit model the UK is aiming for. We’ll have to wait for a speech from PM May slated for mid-late February to get some initial clues here.

So with nothing new – and with the Brexit countdown clock continuing to tick – it’s perhaps not that surprising that BoE officials have done little to talk up the possibility of a February hike. The closest we’ve got to a rate hike signal so far this year is from Deputy Governor Broadbent, who when asked about the chances of a hike in 2018, said “Well, who knows. … we said over the three-year period… I think we had another two or three”.

We suspect the Bank will keep its cards equally close to its chest at this next meeting, albeit remaining cautiously optimistic on the direction of travel in the negotiations. But by the time May’s meeting rolls around, we’re likely to have a transition period agreedin- principle (given firms have made it clear they’ll start preparing for the worst if there is no news by March). In theory, we’ll also have further clarity on the UK’s choice of trade model. We’ll also have a more concrete idea about the direction of wage growth.

Policymakers will also be acutely aware that Brexit talks could become increasingly messy in the lead-up to October, by which time a deal will need to be agreed to allow time for ratification. So May’s meeting could be the most opportune time to hike this year, and for now, we think it’s evenly balanced as to whether they do so or not.

James Smith, London +44 20 7767 1038

China: Strong yuan with good

reason

We have revised our USD/CNY forecast for 2018 from 6.30 to 6.10 based on our view that the central bank wishes to let the yuan be driven by market forces rather than a planned movement.

Dollar weakness is a global trend currently and not just against the Chinese yuan. If the Chinese were to try to fight it other economies would think that the Chinese government is aiming to start a currency war or a trade war. That would not be the objective of the Chinese government, and in fact it has no need to do so while global economic growth is rising. Indeed the implications of yuan appreciation for Chinese exports is likely to be small.

Moreover, there is a seasonal factor in the near term. Chinese exporters usually convert their dollar receipts into yuan before the Chinese New Year to pay “bonuses” to their employees. As the yuan trend is strengthening, some exporters might be chasing the trend to make the forex conversion as soon as possible if they believe that the yuan is to strengthen even more in the near future.

This in fact creates a self-fulfilling cycle to drive the yuan even stronger against the dollar.

But domestic economic data releases do not have much impact on USD/CNY. For example, on 31 January 2018 the official manufacturing PMI was slightly lower than the December data at 51.3 from 51.6. But on the same date, the yuan continued to strengthen against the dollar to break the 6.30 psychological level.

The forex market seems to understand that unless there is an unexpected downturn shown in Chinese data the currency will mostly follow the movement of the dollar index.

That means external factors play a more important role in gauging the trend of yuan. Our house view on the EUR/USD is 1.30 by the end of the year, which indicates a weak dollar trend in 2018.

Would the Chinese government prefer a strong yuan to a weak yuan? We think so. This comes from its concern about capital outflows in 2016 and 2017. And we do not think that this worry has gone. The restrictive measures on capital outflows in still in place.

There is one more worry for the central bank this year. That is hot money inflows, which have been forgotten by the market for years. We believe that a comeback of the idea of hot money inflows in 2018 is likely. Given the wide interest rate spread between China and the US and also China and Europe, and the yuan appreciation trend, hot money may start flowing into China’s stock and bond markets. If so, then we would likely see the central bank work with other financial regulators to step in to rein in the inflows. It could be intervention in the forex market, but it could also be administrative restrictions or window guidance.

All in all, we do not think the central bank intends to intervene at a particular level of USD/CNY. But it will certainly monitor the scale of capital flows (both inflows and outflows). Either too little or too much would be troublesome.

Iris Pang, Economist, Greater China, Hong Kong +852 2848 8071

Japan: Stealth tightening

Market chatter is mounting about the possibility of the Bank of Japan (BoJ) changing its accommodative monetary stance later this year – a possibility that Governor Kuroda himself seemed to concede, when he remarked at Davos that progress had been made towards achieving the BoJ’s 2% inflation target.

That claim is highly disputable. What is not disputable, is that Japan has been on an unprecedented growth spell for almost two years now. Our guess is that we may be due a quarter of upset soon. But that owes more to the vagaries of Japanese data and seasonality than to any genuine slowdown. The underlying story has indeed improved.

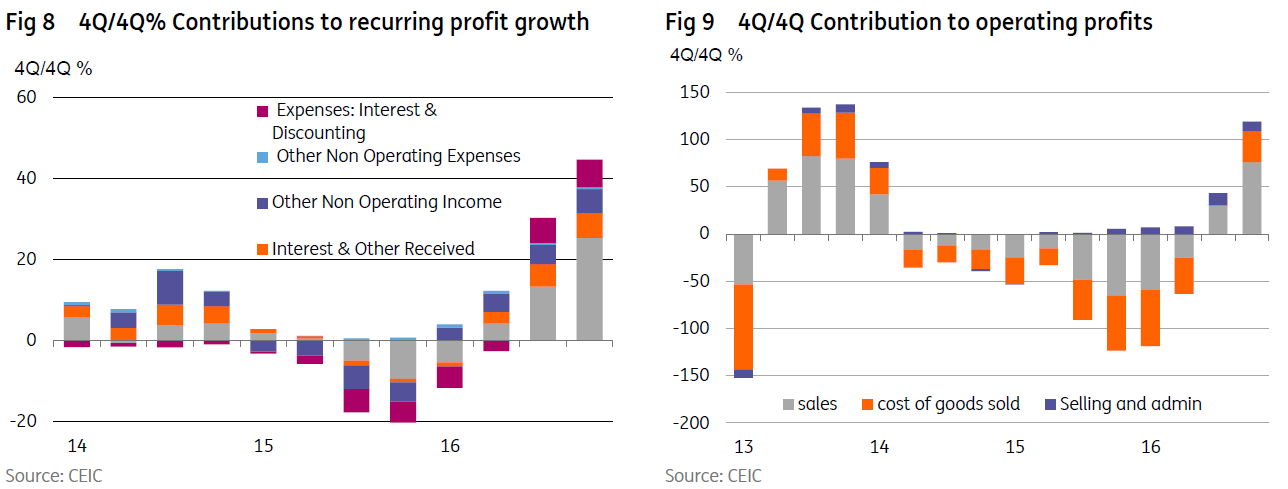

To see what is driving this, we go back to first principles and look at corporate profits. It is from these that Japan’s business cycle stems – profits beget investment which begets employment and so wages and consumer spending and so on.

The profits data paints a very interesting and positive picture, which differs between sectors. Four-quarter profit growth for Japan is close to 18% and has picked up sharply from its recent trough in mid-2016. But the split between manufacturing and nonmanufacturing shows that this pick up is almost entirely a manufacturing phenomenon.

In the manufacturing sector, profit growth on the same basis is more than 40%, of which the lion’s share is operating profit (so not flaky interest or other non-operating incomes that come and go). And crunching the numbers still further, we find that this operating profit is largely a sales driven phenomenon (global demand) though bolstered by a contribution from sales costs and admin efficiencies (robotisation, automation perhaps?).

With underlying strength like this, and strong pressure from Abe to pass on profitability in higher wages (Abe has been calling for a 3% wage rise from firms this Spring wage round), the probability of wages feeding into Japan’s resilience and underpinning growth still further has risen substantially.

Back to the inflation story, and really not much has changed, though the Tokyo figures indicate that headline national inflation will push meaningfully above 1.0%YoY next month. It may rise a little further on base effects through the early part of this year before settling back below 1.0% in 2H18. The pertinent question though is “So what?”. And with corporate growth and the labour market in great shape, it is little wonder that some are speculating about the end of QQE.

Our best guess as to how this comes about is that later this year, and probably under cover of ECB tapering announcements in 3Q/4Q, the BoJ quietly formalises their “underpurchase” of assets relative to their stated aim of buying JPY80tr per year. They are now buying only at about a JPY45-50tr rate, and so that becomes the new target without any change in actual purchases. Later on, the BoJ quietly slows the pace still further, and later still, formalises this again. In this way, it can slowly ratchet down their QQE until they eventually stop buying altogether.

We see a very strong likelihood that such action will feed through into JPY currency strength. But as the profit data shows, ‘Japan.Inc’ is in a very favourable starting position for this, and will still likely be making profits if the JPY breaks through 100.

Rob Carnell Chief Economist, Asia Pacific +65 6232 6020

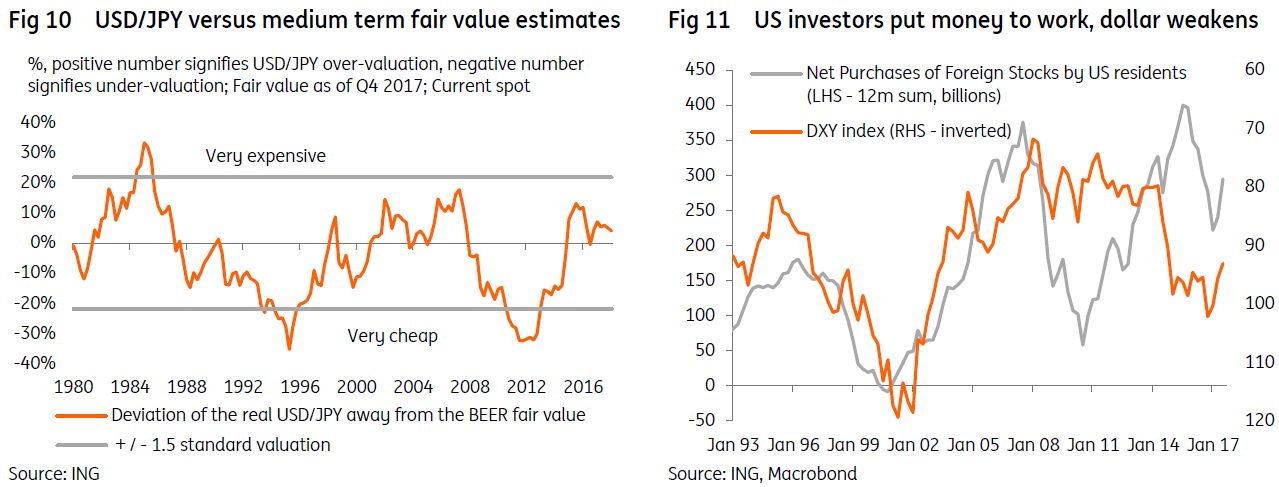

FX: Protectionist risk premium in $

The year has started strongly for risky assets – especially equities. The theme of synchronised global growth, re-rating stories outside of the US and dollar weakness is now a familiar one. We have characterised this as a ‘benign decline’ in the dollar and it is on this which we base our year-end EUR/USD forecast of 1.30.

Yet over recent weeks we have also seen the emergence of some less benign factors such as US protectionism and a mercantilist approach to dollar policy. We now expect investors to build a protectionist risk premium into the dollar, prompting us to revise our USD/JPY forecasts lower.

Let’s look at the two key developments here: (1) President Trump agreeing to antidumping tariffs to protect US manufacturers of washing machines and solar panels; and (2) Treasury Secretary Mnuchin’s comment that a weaker dollar is good for trade.

Both developments could be dismissed as ‘noise’. We would counter that: (1) this is the first time these particular safeguard tariffs have been used since 2002; and (2) President Draghi did not regard Mnuchin’s remarks as casual and instead publicly rebuked him for seemingly encouraging a weaker dollar for trade gain.

In particular Mnuchin’s remarks recall a very similar (and failed) dollar policy employed by the US Treasury in the early-1990s. At the time it was seeking to narrow the US trade deficit with Japan. Having encouraged a weaker dollar in 1993/early-1994 and inadvertently contributed to a Treasury market sell-off, it took well over a year for the Clinton Administration to put the genie of a weaker dollar back into the bottle – and what we now know as the US Treasury’s strong dollar policy was born in April 1995.

How much could the risk premium damage the dollar? Back in the early-1990s, USD/JPY traded more than 30% below ING’s fair value estimate based on medium-term fundamentals. That fair value calculation now stands at 105 – suggesting our downwardly revised year-end target of 100 is not particularly excessive. It also reflects the fact that the world economy is now in a lot better shape than the early-1990s.

The protectionism story aside, it still seems investors are willing to put money to work. US Exchange Traded Fund (ETF) flow data shows continued strong demand for US, Emerging Markets, European and Japanese equities (in that order). Assuming global activity remains on an upswing, we expect US investors to continue to put money to work overseas – keeping the dollar on the back foot. We retain EUR/USD targets at 1.30 for end-2018 and 1.35 for end-2019.

Chris Turner, London +44 20 7767 1610

Rates: Steady climb is best

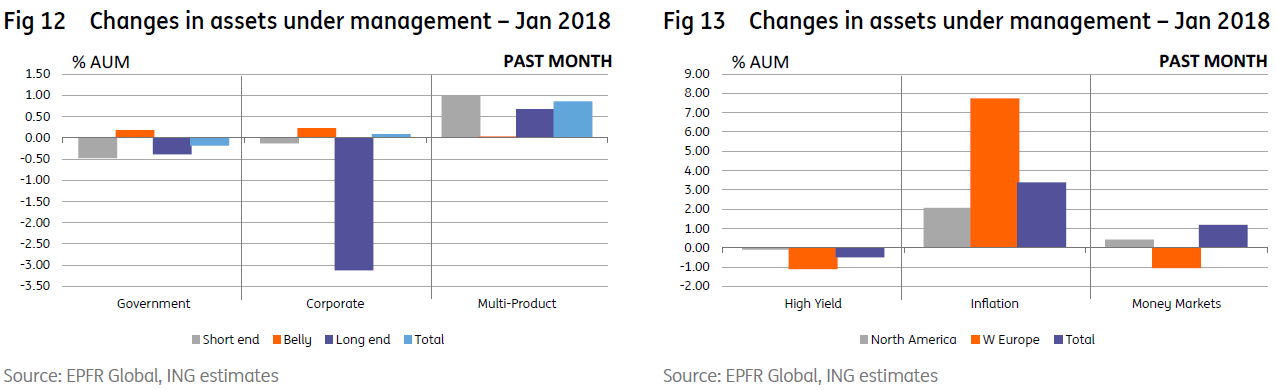

The ratchet higher in market rates has been both persistent and impressive, but not aggressive. We note the following trends in market flows:

- Risky assets have shown a tolerably calm reaction to date, with emerging markets in particular continuing to see decent inflows.

- Flows into inflation funds indicate a reflationary tendency, and no doubt will be welcomed by the likes of the ECB.

- Outflows from long end funds gel with this theme, as this reflects a reduction in nominal interest rate exposure (positioning for higher rates).

Bottom line, the market discount is for more inflation and higher rates; but not too much, as too much would prove disruptive for core rates and, by extension, emerging markets, and that has not been the case so far.

The inflow to inflation in the past month contrasts with the ongoing outflow from developed markets high yield (Figure 12). The other notable flow has been out of long end funds. There has been a slow but steady trickle out of long end government funds since the turn of the year, which is code for a silent build in duration shorts. More recently there has been some large liquidations seen on long end corporate funds (Figure 13).

In the Eurozone we note mild outflows, stretching across all markets. There has been no particular core/periphery story to tell here. There is a suspicion of relative value in play here, as Eurozone rates have come under pressure, leaving investors with a combination of low rates and tight spread to contend with.

The overall sense from these market flows is one of a new and likely structural theme of higher market rates, and this in fact makes the delivery of rate hikes from central banks that bit more in sync with a growing reflationary discount. Provided the rise in the 10yr Treasury yield is capped by 3% there should not be a big negative reaction from risk assets. This is our central expectation.

However, in a scenario where the 10yr yield were to break above 3% and threaten a move the 3.5% we would then move into a less palatable set of circumstance for both equities and emerging markets. But for different reasons – for equities dividend yields would begin to look rich versus bond yields, while for emerging markets the concerns would be performance and worries would over re-funding costs and/or for a dollar bounce (not our central view). Steady is best, and a cap at 3% would calm nerves.

Padhraic Garvey, London +44 20 7767 8057