The growing inflation puzzle

The financial markets have started 2018 where they left off in 2017. Manifold geopolitical risks continue to be treated as background noise, and a stream of mildly positive growth surprises continue to keep asset prices buoyant. In our view, forecasters may still be underestimating the upswing, in which case a bigger threat to the markets’ mood may come from inflation. 2018 may give some answers to the puzzle as to why inflation hasn’t already stirred.

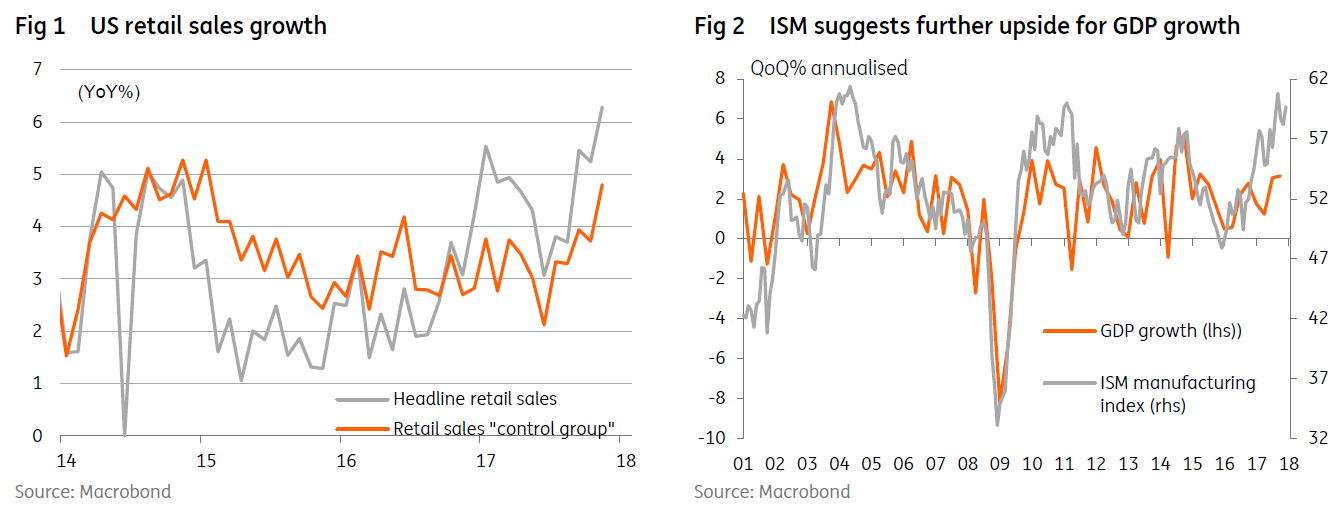

The US growth story is going from strength to strength. The domestic economy is firing on all cylinders and the external picture continues to brighten. This is creating a sense that a pick-up in inflation may not be far away. Core inflation rates remain low for now, but, with a tight jobs market risking higher wages and the strength of the housing market set to feed through into a stronger contribution from shelter, we doubt this will last. Moreover, with oil prices rising and business surveys suggesting price pressures are building, we see upside risks to our forecast for three 25bp Fed interest rate rises this year.

Politics remains a risk with President Trump sounding increasingly bellicose in his approach to North Korea, Iran and Pakistan. For now markets are brushing this aside. Instead, they are focusing on the windfall from tax reform that will likely lead to share buybacks and more M&A activity. But sentiment could change quickly should talk turn to action.

The Eurozone recovery seems to be going into overdrive, with the latest indicators suggesting a 3% annualized growth pace around the turn of the year. While we doubt that this pace will be maintained throughout the year, we believe that GDP growth in 2018 will be at least as good as in 2017. While inflation pressures are now becoming more visible, the ECB is unlikely to end its quantitative easing (QE) bond purchasing programme prematurely.

Inflation, or more precisely wage growth, will be key to whether the Bank of England will hike interest rates this year. There have been some better signs of late, but we’re still not fully convinced pay will pick up quite as fast as policymakers hope. That, and the fact UK that growth is set to stay sluggish this year means a rate rise is not yet guaranteed.

China is preparing to smooth out liquidity tensions around the Chinese New Year. We suspect the usual high money market rates won’t be repeated. We also see that the regulator is closing loopholes regarding capital outflows. These measures highlight how careful the central bank is being in the year of financial reform.

The possibility of a rate rise in Japan is also rising. However, we suspect that the Bank of Japan (BOJ) will wish to see not just current real growth rates maintained, but some uplift in inflation before it moves starts to move on its Quantitative and Qualitative Monetary Easing (QQE) with Yield Curve Control.

Despite all the positive noise coming out of the US, the dollar is not rallying. In our opinion this is because there are better re-rating stories in overseas economies – especially in Europe. We maintain an end 2018 EUR/USD forecast of 1.30. The upside break-out should come in 2Q18 when Italian political risk has passed and the market is once again debating the end of the ECB’s QE programme.

US: “It’s great…”

Last month we suggested that 2018 will see President Trump get the 3% growth he promised during his election campaign. The data since then has only reinforced this view. The domestic economy is in excellent health with housing numbers, retail sales, the state of the jobs market and business surveys all suggesting that momentum is very strong.

Trump has also got his tax cuts through so there is going to be more cash in the pockets of businesses and consumers, which will add to the upside potential for investment and consumer spending. Equity markets will also be kept aloft by the potential for share-buybacks, special dividends and the prospect of more M&A fuelled by the corporation tax cut and repatriation of foreign earnings.

The external economic environment also looks good. Forecasts for economic activity in Europe and Asia continue to rise, while the dollar’s 10% trade-weighted decline since Trump’s inauguration means that the US is in a competitive position to take advantage.

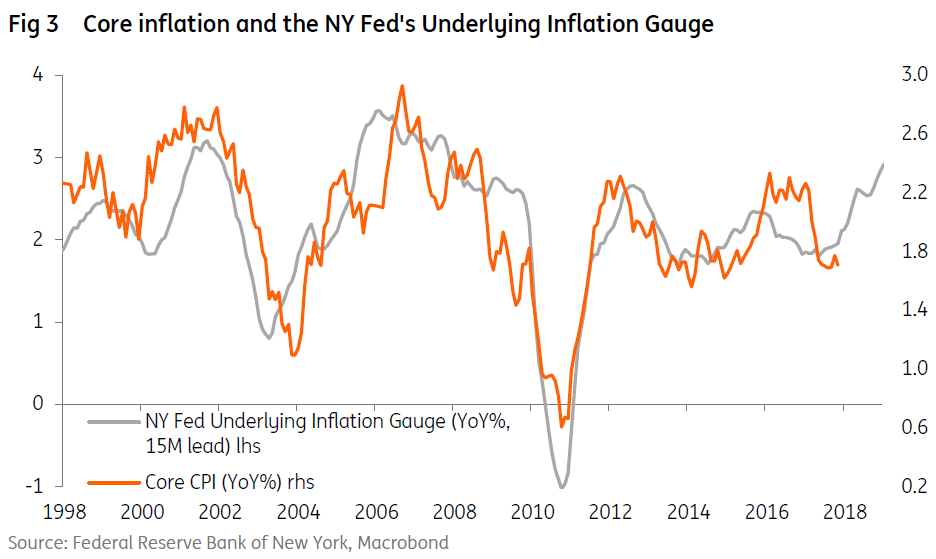

This strong growth, tight jobs market, soft dollar environment hints at upside risks for inflation too. Headline CPI inflation is currently at 2.2% YoY while core, excluding food and energy, is at 1.7%, but we think the latter will soon be above the Federal Reserve’s 2% target. Apparel prices have been surprisingly weak, while mobile phone charges have dragged the headline lower temporarily. These factors will unwind this year.

Housing too is likely to exert more upward influence given the strength in activity. This component accounts for over 40% of the CPI basket and is currently running at 2.8% YoY. Given the recent MoM% price changes we see the annual rate of this key component breaking above 3% very soon. On top of this, geopolitical uncertainty, which we believe Trump is helping to stoke, and strong global growth means that we could see oil prices remaining high. This will add to the upside for inflation in 2018.

This prognosis is also receiving support from the New York Federal Reserve, which have created a new underlying inflation gauge [1]. This is a model-based approach that provides a “more timely and accurate signal for turning points in inflation” using both prices and “wide range of nominal, real and financial variables”. The NY Fed’s model suggests we could see core inflation heading sharply higher this year.

In an environment where growth is strong and inflation is likely to rise above the Fed’s 2% target, we continue to expect three 25bp rate hikes this year. Jay Powell takes over from Fed Chair Janet Yellen at the end of February and there are going to be several other changes in terms of Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) voters. Two of the most dovish voters in 2017 – Neel Kashkari and Charles Evans – are to be replaced by two relatively hawkish figures in Loretta Mester and John Williams.

There is also a new vacancy at the NY Fed with William Dudley standing down from mid- 2018 while there are still three vacancies on the Fed’s Board of Governors even if Trump’s latest pick, Marvin Goodfriend, is approved by Congress. The result is a smaller and more hawkish committee in 2018 versus 2017.

That said, we feel that the imminent changes at the top of the FOMC could result in a pause in the first quarter as Jay Powell finds his feet, before consecutive quarterly hikes through the rest of the year. The skew for where we see the risks to our forecasts is to the upside though. The Fed remains nervous that the flat yield curve and dollar weakness means financial conditions remain loose, suggesting a more pressing need for Fed action at the short end. There is also a wariness that the prolonged period of ultra-low interest rates has changed household and corporate behaviour and could lead to increased leverage with “adverse implications for financial stability”. As such, we are open to the idea of a fourth Fed rate rise this year.

For now though, we think that the Fed’s decision to shrink its balance sheet will exert some upward influence on longer dated yields through the year, which will reduce the necessity for that additional hike. With inflation likely to rise and the significant tax cuts likely prompting a wider fiscal deficit and more bond issuance the result is that the 10Y yield may edge towards 3% by year end.

In terms of politics, January is likely to be another busy month. The focus on tax cuts meant that the process of agreeing a budget was delayed, which also necessitated yet another temporary reprieve regarding the debt ceiling. The deadline to avoid a potential government shutdown has now been pushed back to 19 January.

There does seem to be bi-partisan agreement to increase spending, but the balance – Trump favours more of a focus on defence – is opposed by the Democrats. Consequently while we feel progress can be made, there is probably too much work to do for it to be signed off by 19 January. Instead, the situation will likely require another short-term funding bill that will give breathing space through to March.

We will also be looking to 30 January when President Trump will give the State of the Union address. Now that his tax reforms have been passed he is keen to make progress on another election campaign promise – infrastructure spending. He may set out more details of what he hopes to achieve and there is bi-partisan support for more spending on the nation’s roads, air transport and rail networks, although there is less for “the Wall”. However, there is a lot of disagreement on how contracts would be funded and Democrats are reluctant to give him an “easy win” ahead of November’s mid-term elections. Nonetheless, if he can make progress, billions of dollars of infrastructure spending will be a further boon for the economy.

James Knightley, London +44 20 7767 6614

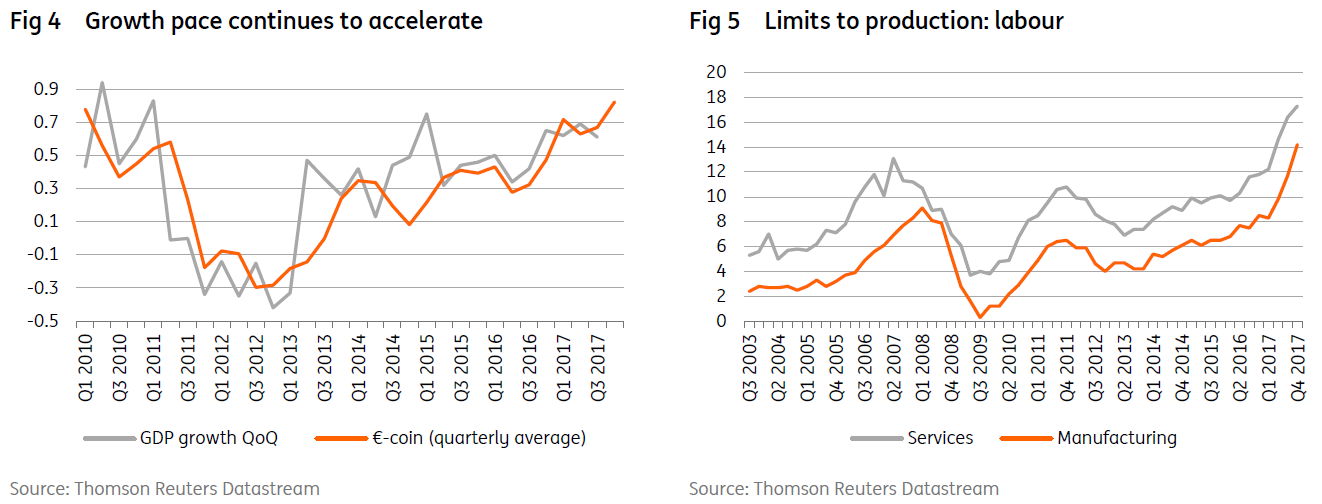

Eurozone: Going into overdrive

The Eurozone recovery seems to be going into overdrive. The €-coin indicator, a proxy for the underlying growth momentum, hit 0.91% in December, suggesting an above 3% annualised growth pace. While we doubt that this pace will be maintained throughout the year, we believe that GDP growth in 2018 will be at least as good as in 2017.

With employment rising 0.4% in the third quarter, consumer confidence in December hit its highest level since January 2001, boding well for consumer expenditure. Rising supply constraints and generous financing conditions are likely to continue to underpin the business investment revival. Notwithstanding the strong euro, export perspectives remain upbeat. The rebound in global investment is particularly helpful for Eurozone exports. No wonder that most cyclical indicators are close to historical highs. The PMI indicator for the manufacturing industry in December hit the highest level since the series started in mid-1997.

True, politics could still cause upsets, but probably not enough to spoil the growth party, we believe. With the pro-independence parties still holding a majority after the regional elections in Catalonia, the problem is not going to be solved rapidly, though we don’t think that the Spanish economy will suffer significantly from the current stalemate. That said, some negative impact cannot be avoided. The budget for 2018 has still not been approved, as the Basque National Party is refusing to support the draft budget of Rajoy’s minority government, as long as the Catalan issues have not been settled.

In Germany, there is still no new government, which is quite unusual for the country. It is still unsure whether the SPD party members will give the green light to another grand coalition. The biggest problem that the current power vacuum creates is European, as in the current circumstances Chancellor Merkel doesn’t have a mandate to support Emmanuel Macron’s ambitious reform plans for the Eurozone. Finally, 4 March has been set as the date for the Italian general elections. For now, it looks likely that there will be no clear winner, making the formation of a workable coalition difficult, but we consider the likelihood of an anti-European coalition to be quite small (about 10%).

Of course, we cannot exclude sudden shocks in financial markets, which could also temper the growth momentum. Indeed, it would be a surprise if the current low volatility and depressed risk premia remained in place for the whole of the year. In that regard, it still looks wise to not to overdo the expectation of continuing above potential growth. That said, we now believe that 2018 GDP growth will come out at an above-consensus 2.4%, on the back of a strong base effect and the current growth momentum. From the second half of the year onwards growth is likely to start converging gradually towards the longer term growth potential, which for the Eurozone is below 2%.

With supply constraints getting more important, it looks as if wage growth will start to pick up in the course of 2018. In the PMI Manufacturing Survey businesses reported higher rates of inflation in both output prices and input costs as supply chain pressures increase, with average vendor lead times lengthening to one of the greatest extents on record. But even then, the European Central Bank’s consumer price inflation target is unlikely to be reached in 2018, so justifying its loose monetary policy.

However, on the back of the stronger growth and increasing inflation, the calls to end the quantitative easing (QE) bond buying programme in September 2018 will grow louder. We maintain our belief in a short extension, but in December the net asset buying should have ended. Excess liquidity is likely to hit €2000 billion in the course of 2018 and start only to decline very slowly in 2019, keeping money markets interest rates in negative territory until the summer of 2019.

Peter Vanden Houte, Brussels +32 2 547 8009

UK: A year of tough decisions

As a turbulent 2017 finally drew to a close, politicians on both sides of the channel were finally able to blow a sigh of relief. After months of deadlock, an agreement was reached on the UK’s financial liabilities, citizens’ rights, and ultimately most contentiously, the Irish border.

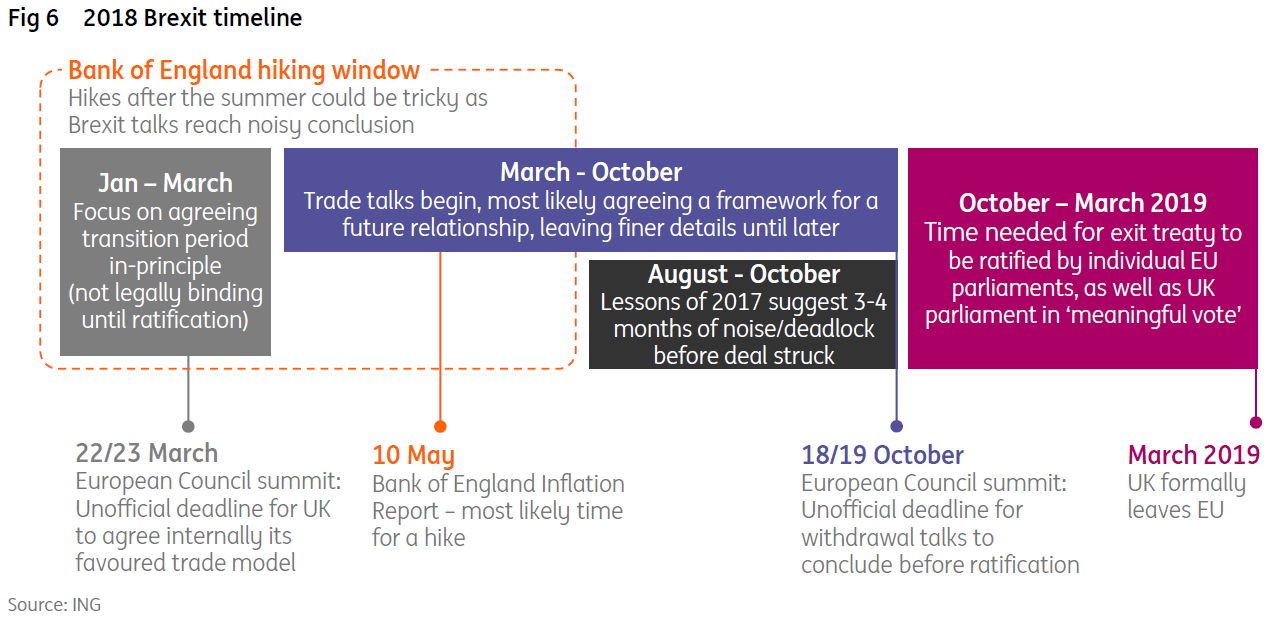

December’s breakthrough means that a transition period looks set to be agreed by the end of the first quarter. Admittedly such an agreement won’t be legally binding until the full exit treaty is ratified later this year. But a firm commitment by both sides that there will be a ‘status quo’ transition period until late 2020/early 2021 should be enough to prevent firms enacting their ‘no deal’ contingency plans.

Of course, there are still plenty of challenges looming this year – perhaps the biggest of which is whether a trade deal can actually be agreed in full before March 2019.Trade talks are unlikely to begin before March, before which time the UK will internally agree on the trade model it’s aiming for. The talks will need to be wrapped up by October’s European Council summit, to allow time for each member state to ratify a deal as well as for the UK parliament to hold it’s ‘meaningful’ yes/no vote on what is agreed.

That leaves an extremely narrow six-month timeframe for trade negotiations, which makes it more likely that only the broad framework of a trade deal will be agreed before the UK exits the EU. This implies that the finer details would then be thrashed out during the transition phase.

This raises the question of whether a two-year transition period will be long enough for businesses, or indeed the customs infrastructure, to adjust to the new relationship. It’s also possible that, without knowing the finer details of the UK’s future trading relationship, firms could remain cautious when it comes to investment (particularly that with a longer-term horizon)

This is one reason why economic growth is likely to remain fairly sluggish this year. Consumer spending is also set to remain under pressure, with disposable incomes likely to be (at best) flat. This will limit growth to around 1.4% this year, giving the Bank of England a conundrum when it comes to deciding whether to hike rates again this year.

Ultimately, wage growth will be pivotal to the decision. There has been some slightly better news on this front, with signs that skill shortages in certain sectors are prompting firms to boost salaries to retain staff. To take one example, the shortage of UK lorry drivers increased by 49% [2] in 2017 as the pool of talent shrinks, which led to firms to offer up to 20% premiums on hourly rates.

That said, with the cost of raw materials and energy picking up, and demand still fairly anemic in many sectors, some firms are likely to take a more conservative approach with eye on maintaining margins. The Bank of England is optimistic about wage growth, although we still feel it may not take-off quite to the extent its forecasts assume.

So with growth likely to remain sluggish and uncertainty over the path of wage growth, we still think a rate hike this year cannot be guaranteed, though this is increasingly a close call. But whatever policymakers decide, we think they have a fairly narrow window before the summer if they want to squeeze in another rate rise. The lessons of the past few months tell us that, prior to some kind of deal being struck in October, there could be 3-4 months of deadlock and noisy negotiations. This leaves February, or more likely May, as possible candidates for another rate hike this year.

James Smith, London +44 20 7767 1038

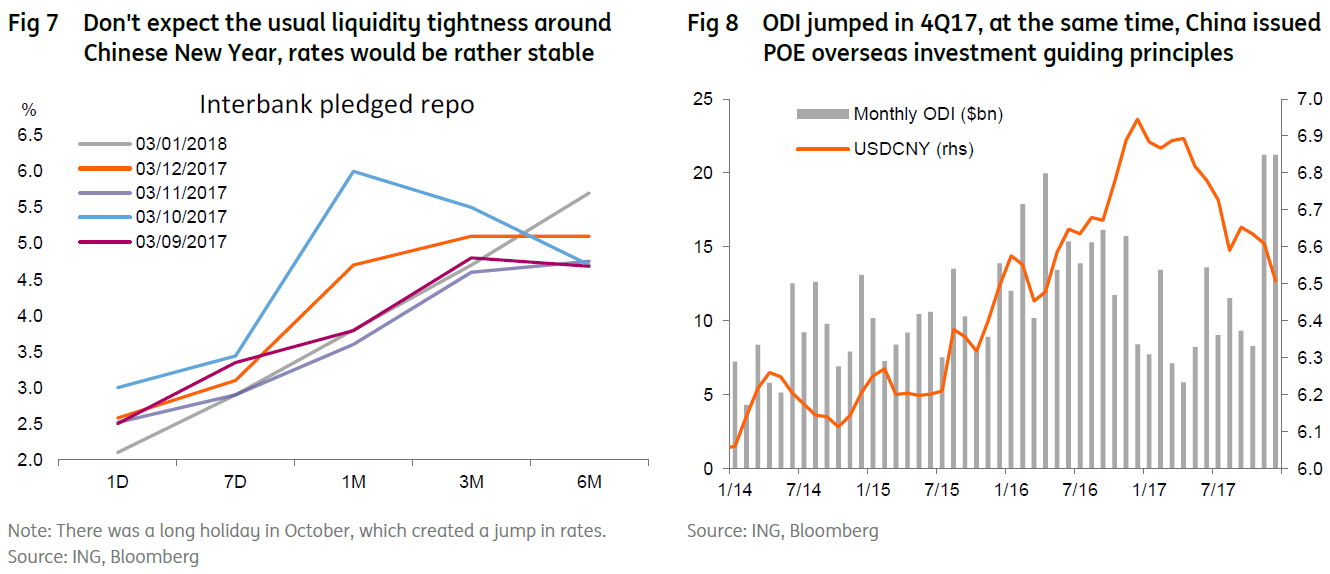

China: Central bank pre-empts risks

Near the end of 2017, the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) announced a provisional arrangement on reserve requirements. Any nation-wide banks that need cash around the Chinese New Year can enjoy a 30-day two percentage point cut in their reserve requirement ratio, which is now 17% on deposits. This is designed to avoid cash hoarding behaviour by banks before the Chinese New Year. This year’s Chinese New Year holiday period falls between 15 to 21 February.

This special measure is equivalent to a 30-day liquidity injection of around CNY 1 to 2 trillion in the banking sector. Through the interbank market, this holiday liquidity injection should ease financial tension for the broader financial sector, including non-bank financial institutions.

Consequently, we do not expect any spikes in short-term interest rates in the money market around the Chinese New Year. Moreover, this practice, if it works for the Chinese New Year, could be copied for other long holidays.

We would like to highlight that this forward-thinking policy indicates that the central bank will be remarkably careful this year to not let interbank interest rates rise too speedily, although the market will have to get used to this pattern around holidays. This demonstrates the central bank is taking the government’s plan to “avoid systemic risks” seriously.

But no spikes in money market rates does not mean interest rates will not increase in 2018. To facilitate financial deleveraging we forecast the central bank will hike three times, each by 5bp on 7D repos to stabilise interest rate spreads between the yuan and the dollar. It is less likely that each hike would be 10bp as the central bank would worry that the money market could overreact and spikes in money market could arise.

It is not surprising that the central bank is so cautious as financial deleveraging reforms are on the way, meaning liquidity can only be tighter in 2018 compared to 2017. Financial regulators, including the PBOC and the banking regulator (CBRC), have set out new rules as well as issued policy consultation papers to guide banks and financial institutions to do their businesses more prudently. These include guiding principles of asset management business conducted by financial institutions, including insurance companies, as well as regulating businesses between trust companies and banks so that off-balance sheet items at banks could shrink. And it has separately given banks one year’s preparation time to build interest rate risk management models. Risks in the financial sector should diminish when more financial regulations are in place. But markets may worry that some marginal financial institutions would be prone to higher credit costs and liquidity risks.

Another “avoid systemic risks” policy is to get net capital inflows into the economy. In essence, capital outflows mean drainage of liquidity from the domestic market to overseas markets. Apart from advising private corporates to invest sensibly overseas, the central bank has set personal overseas ATM withdrawal limits at CNY100,000 per year. There was no such limit before, though the cap of US$50,000 personal overseas spending has been left unchanged. We believe that the regulator is closing these loopholes to stem capital outflows.

Another way to attract capital inflows is to keep the yuan appreciating. But over-appreciation would be appealing to speculative money, which the regulators would not welcome. So we forecast a slower yuan appreciation rate of 3.0% in 2018 compared to 6.6%. This is equivalent to USDCNY and USDCNH would reach 6.3 by end of 2018.

In short, we believe that liquidity risks or financial counterparty risks are not rising in China. While financial deleveraging reform is imperative in 2018, regulators are aware that they need to take cautious measures to avoid systemic risks. This also explains our forecasts of three 5bp rate hikes to stabilise interest rate spreads between the yuan and the dollar. On top of this, to continue to attract net capital inflows, we forecast USDCNY and USDCNH to appreciate 3% from 6.5 in 2017 to 6.3 in 2018.

Iris Pang, Economist, Greater China, Hong Kong +852 2848 8071

Japan: The problem of success

With only one slight blip in 3Q16, when the economy grew at 0.9% QoQ (annualised), Japan has recorded growth of above 1.0% (actually at or above 1.4%) in each of the last seven quarters. The revised 3Q17 GDP growth figures of 2.5% come hard on the heels of a 2.9% growth rate in 2Q17. Full year growth looks likely to come close to 2.0% (ING f 1.8%), which would be the strongest growth performance since 2010, when Japan emerged from the global financial crisis.

The extent, and persistence of Japan’s growth is leading some to question what this means for Bank of Japan (BoJ) policy. Currently, this targets ten year Japanese government bonds (10Y JGBs) at about zero percent, and keeps the interest rate on policy-balances held by banks with the BoJ at -0.1 %.

Like the yields on other G-3 bonds, JGBs have not escaped the recent rise in global yields, nosing up to about 0.05% from a recent trough of about 0.01%. That owes partly to overseas influences, the markets’ reluctant acceptance that the Fed’s ‘dot-plot’ of interest rate expectations is not so unrealistic and the beginning of the end of quantitative easing in the Eurozone.

But is it reasonable to imagine that the BoJ could follow suit in 2018? Shorter maturity Japanese government bond yields remain negative, but they too have been nosing higher, suggesting some expectation of higher rates in the not too distant future. Sure, growth data are remarkably strong, and matched by similarly tight labour market data, but the BoJ has so far made little headway in raising inflation towards its 2% target.

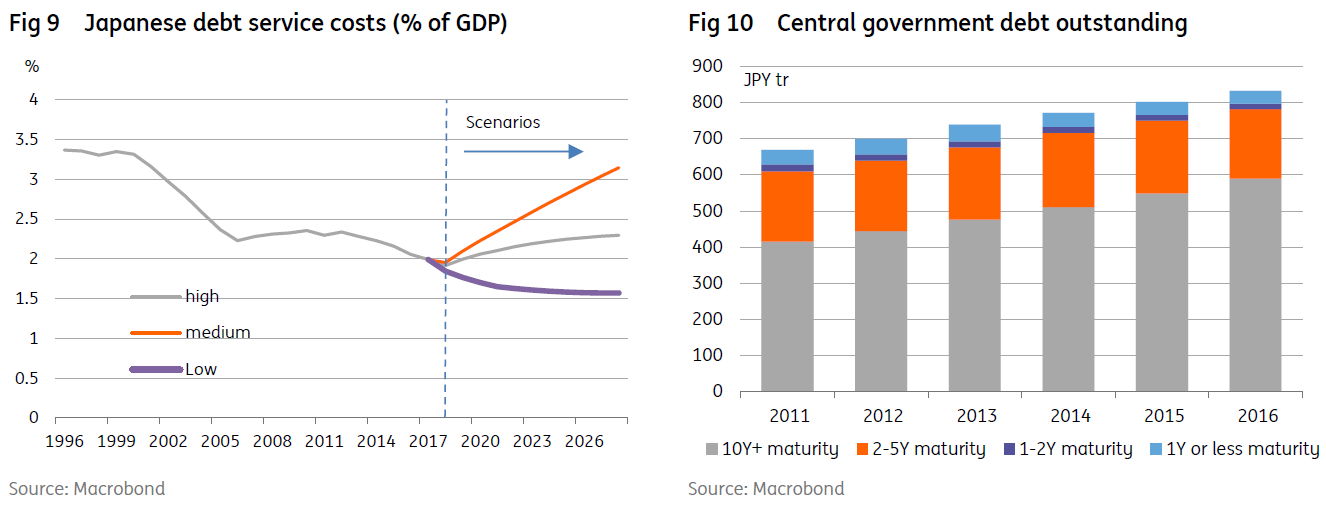

If Japan does eventually make some progress on inflation, or the BoJ eventually decides that 2% is simply the wrong inflation target and starts to raise rates, what then? When total government debt is in excess of a quadrillion yen (more than double GDP), shouldn’t this cause problems?

What happens next depends on a number of moving parts, none of which are clear. Does inflation actually rise, lifting bond yields, but also likely raising nominal GDP. Does real GDP growth remain good, but inflation, and bond yields remain low, even as the BoJ hikes rates? Do we get something in between?

With the lion’s share of outstanding Japanese government debt of 10 years of longer maturity, even a return to 2% inflation and benchmark bond yields rising to a similar level will take some time to feed through into the government’s effective debt financing rate. But in our “high” scenario, where bond yields and inflation both rise to around 2.0%, this adds a full percentage point of GDP to government debt service costs by 2028. Still, this isn’t a catastrophe, and if government revenues are also rising in line with nominal GDP, this should be quite manageable. In our low scenario, where inflation and bond yields remain low, despite good real GDP growth, then the debt service costs will simply converge on the weighted average of long- and short-term bond yields times the debt stock as a proportion of GDP.

There is, therefore, a perfectly plausible scenario in which the BoJ hikes rates this year. We don’t think it will, however. We suspect the BoJ will wish to see current real growth rates maintained for longer before relinquishing the comfort blanket of QQE. And see some improvement in inflation. And we doubt the latter will be forthcoming, even if the former remains strong. But it is not as silly an idea as it once sounded.

Rob Carnell Chief Economist, Asia Pacific +65 6232 6020

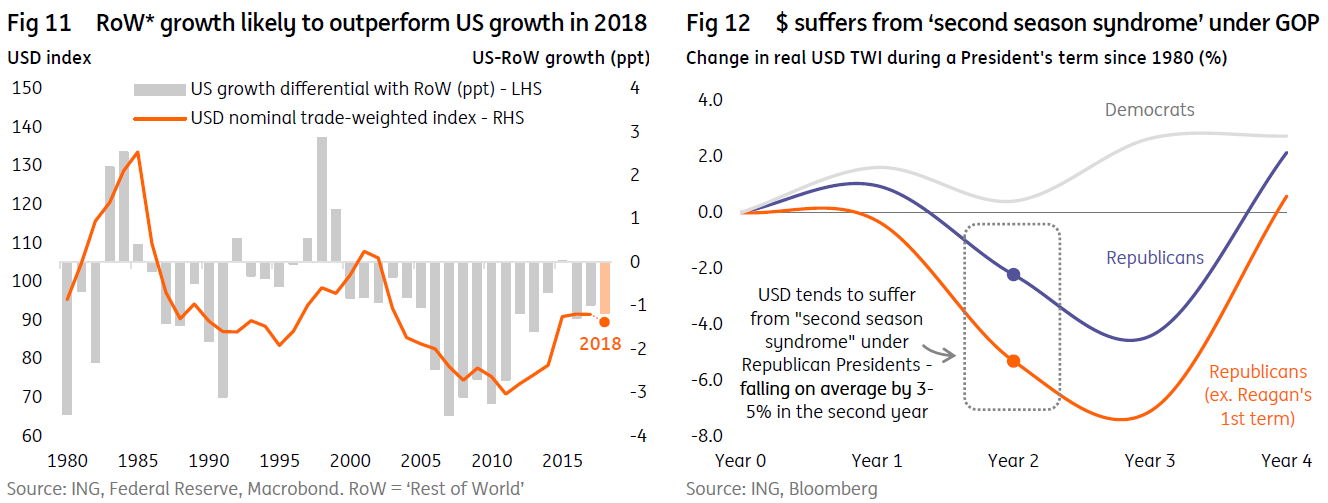

FX: Why the dollar need not rally

One of the surprises towards the end of 2017 was how the dollar failed to derive much benefit from improving US growth prospects and the move towards pricing three Fed hikes in 2018. In our opinion that dis-connect was driven by the re-rating of growth stories overseas – especially in Europe. We expect this trend to continue in 2018 and maintain an end-year EUR/USD forecast of 1.30.

Last year we were making the point that the 6% decline in the broad dollar index was driven by the re-rating stories in the likes of CNY, EUR, MXN and CAD (comprising 64% of this index). We expect these trends, ex MXN, to largely continue – where early to mid-cycle recoveries are favoured, particularly by equity investors, compared to the later cycle story in the US.

We would also argue that comparisons between Trump’s reflationary policies are nowhere near those of Ronald Reagan in the mid-1980s, such that the dollar does not need to see a Reagan-style rally on US tax reform in 2018. Importantly back in the early 1980s the EEC (the pre-cursor to the EU) unemployment rate was doubling, delivering a decisive growth differential between the US and Europe.

Fortunately Europe is in a lot stronger position today and rising growth rates in major trading partners stand to limit the extent of US macro outperformance.

On that subject, President Trump will welcome stronger overseas growth but will not want to see the dollar strengthen meaningfully. In fact going back to the 1980s, the second and third years of Republican Presidencies have actually been most negative for the dollar. In the run up to mid-term election it would not be a surprise to see Washington return to the issue of unfair trade practises and, by implication, the need for stronger currencies amongst key trading partners in Europe and Asia.

Probably the biggest risk to our baseline of a benign dollar decline would be a US inflation break-out, prompting a sharp acceleration in Fed tightening and an inverted US yield curve – inverted yield curves are typically positive for currencies.

For EUR/USD, we maintain a relatively flat profile through 1Q18 as focus shifts to Italian electoral risks in early March. The upside break-out should come in 2Q18, when the market resumes debate on the end of ECB QE and Bund yields are on the rise. In addition, the EUR should perform well as a safe-haven currency, should the investment environment become more challenging later in the year.

Chris Turner, London +44 20 7767 1610

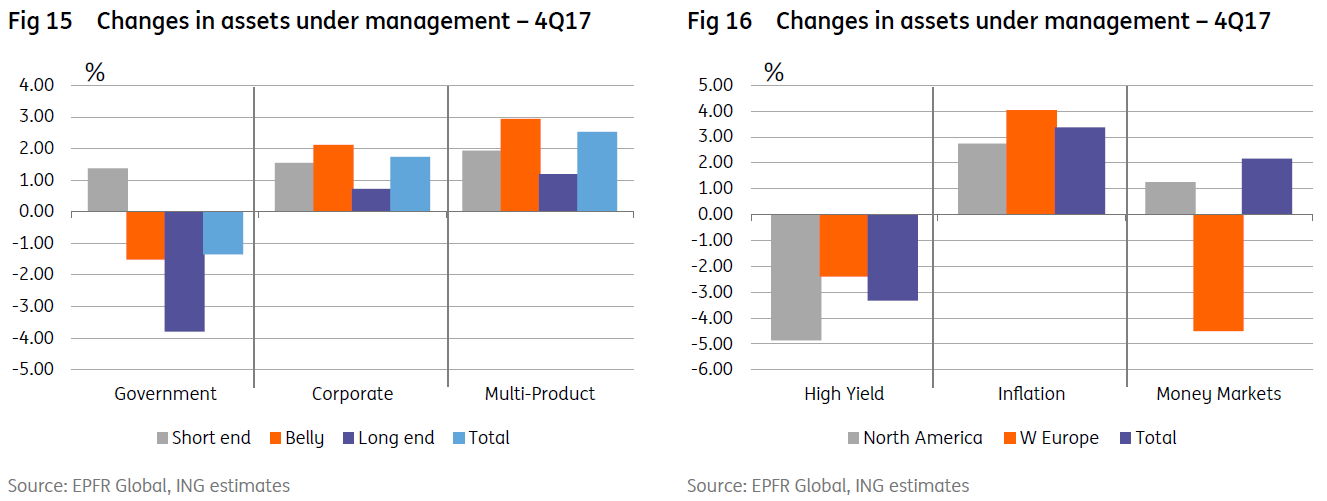

Rates: New year, new money

Away from fundamentals, a key theme in the final months of 2017 was a tendency for market participants to position for higher rates. This can be gleaned from flows data which show a broad increase in holdings in less interest sensitive products (short maturities) and a reduction in exposure to longer duration funds. In fact, over the final quarter of 2017 there was a near 4% liquidation in holdings of long-end funds and a near 1.5% increase in holdings of short-end funds (Figure 13) – effectively the marketplace had been shortening duration and in consequence bracing for higher market rates.

Another notable theme into end 2017 was buying of inflation linked products. Specifically in the final quarter there was a 4% expansion in holdings of European inflation linked bonds (Figure 14), and US inflation linked products saw continued good inflows too. This is important as an indicator of resumed market confidence for a rise in inflation in the months and quarters ahead.

The other theme identified in the illustrations above is one of flows out of high yield and into investment grade corporates (which in fact was a trend seen through most of 2017). There was a mild widening trend into year end, but resumed tightening has been seen since. The launch of new liquid syndicated deals in the next few weeks and through January should sustain a reasonable tone for spreads, at least for now.

Beyond that market participants will be looking for potential catalyst for change. One such excuse comes from looming Italian elections set for early March and thus to be front and centre through February. Another is ongoing US inflation watch, which looks more and more likely to move in the direction of upholding the Fed’s ambition to deliver on the dots for a second year. This is likely in the market psyche, but not discounted yet.

There has been a clear march higher in yield on the front end of the US curve over the past quarter. Meanwhile, the 10yr yield has spent practically the full quarter north of 2.3%, and is eyeing a break above 2.5%. Similar for the 10yr Bund, which is looking comfortable in the 45bp area, notwithstanding the vulnerabilities that obtain from being at the top end of its recent trading range.

Bottom line, the path of least resistance is for a nudge higher in rates. But progress higher will be tempered by new money getting put to work which will be supportive for spreads. That said, the dominant theme should still centre on a mild test higher in yields.

Padhraic Garvey, London +44 20 7767 8057

[1] https://www.newyorkfed.org/research/policy/underlying-inflation-gauge

[2] According to Manpower/Freight Transport Association